Society

73 years ago today: Romania’s Bessarabia was annexed by USSR on 28 June 1940

Reading Time: 4 minutesOn June 28, 1940, the annexation of Bessarabia was carried out by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) under the provisions of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, and was eventually consented to by both the predecessor state, Romania and the international community, in the form of the 1947 Paris Peace Treaty. Under pressure from Nazi Germany, King of Romania Carol II bowed to the Soviet ultimatum of midnight, 26 June 1940, and two days later, after a dramatic Crown Council, Romania surrendered Bessarabia and Northern Bucovina to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, a renunciation that heavily damaged Carols prestige and precipitated his loss of authority and his subsequent forced abdication on 6 September 1940, when the supreme powers of the state were taken over, under military rule, by General (later Marshal) Ion Antonescu.

On June 28, 1940, the annexation of Bessarabia was carried out by the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) under the provisions of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, and was eventually consented to by the predecessor state, Romania (while under Soviet occupation), and the international community, in the form of the 1947 Paris Peace Treaty. Under pressure from Nazi Germany, King of Romania Carol II bowed to the Soviet ultimatum of midnight, 26 June 1940, and two days later, after a dramatic Crown Council, Romania surrendered Bessarabia and Northern Bucovina (today it is part of Ukraine) to the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, a renunciation that heavily damaged Carol’s prestige and precipitated his loss of authority and his subsequent forced abdication on 6 September 1940, when the supreme powers of the state were taken over, under military rule, by General (later Marshal) Ion Antonescu.

Its provisions — as embodied in the status of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (MSSR), a part of the USSR after 1940 -— became null and void on August 27, 1991 by virtue of Moldova’s declaration of independence as a sovereign state.

In August 1940, in the aftermath of the Soviet annexation of Bessarabia, the Supreme Soviet of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR) passed the law on the formation of the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic, with Chişinău (renamed once again Kishinev) as its capital.

Coupled with deportations of resisting landowners kolkhozes, or collective farms, were first organized in November-December 1940, in the immediate aftermath of the Soviet annexation of Bessarabia. The process was interrupted during World War II and resumed actively soon after, sporadically marked by incidents of fierce opposition and widespread manifestations of passive aggression towards the Soviet-imposed confiscation of land.

The communist atheism, an official doctrine of the Soviet regime, also called "scientific atheism," has been aggressively applied to Moldova, immediately after the 1940 annexation, when churches were profaned, clergy assaulted, and again throughout the decades of Soviet regime, after 1944. Starting in the early 1960s, in keeping with directives from Moscow, most of Chişinău’s churches were either pulled down or turned into facilities designed to serve secular or even profane purposes.

The local population, mainly individuals of Romanian ethnicity, were deported to Russia’s Siberia and Cenral Assian Republics. The first wave of mass deportations, linked with atrocities, was executed by the NKVD over a period of 12 months, between June 1940 and June 1941. In the first months of 1941, 3,470 families, with a total of 22,648 persons labelled as "anti-Soviet elements"—mostly landowners, merchants, priests, and members of the urban bourgeoisie—were deported to Kuzbas, Karaganda, Kazakhstan, and other faraway parts of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR), amid reports of atrocities and exterminations. In Chişinău alone, evidence indicates that over 400 people slated for deportation were summarily executed in July 1940 and buried in the grounds of the Metropolitan Palace, the Chişinău Theological Institute and the backyard of the Italian Consulate, where the NKVD had established its headquarters. Historians estimate that just on 13-14 June 1941, some 300,000 persons (about 12 percent of the entire population of the annexed territories) were deported to other regions of the USSR. In Bălţi alone, according to eyewitnesses, almost half of the city’s population of about 55,000 was deported to the interior of the USSR between 14 and 22 June 1941.

A second wave of deportations was carried out beginning with the Soviet reoccupation of Bessarabia of August 1944. It was executed in short and brutal installments over a period of several years by the NKVD and its successor agency, the MVD. The 1949 deportations from the Moldavian Soviet Socialist Republic (MSSR) were carried out under the code name "Iug" (Operation South), which enforced the confidential Executive Decision No. 390-138 issued by the Soviet Union’s Council of Ministers on 29 January 1949. Moscow’s decision was aimed, among other things, at expediting the forced collectivization of Moldova’s agriculture by getting rid of all members of the rural population suspected of resistance to the suppression of private property (see RESISTANCE MOVEMENTS). On 17 February 1949, an action memo signed by Soviet General I. L. Mordovetz, who headed the Chişinău Ministry of Security, indicated that 40,854 persons, most them kulaks, or small landowners, had been earmarked for deportation from the MSSR. Enforcing the secret Decree No. 509 of 28 June 1949 issued by the Soviet authorities in Chişinău, on the night of 5-6 July 1949, 35,796 persons—9,864 men, 14,033 women and 11,889 children—were deported under military escort to several faraway regions of the USSR. On the night of 5 July that same year, some 25,000 Moldovans were deported from Bolgrad, Ismail, and Akkerman and sent to Siberia or Kazakhstan.

The immediate effects of these deportations in terms of eradicating resistance to surrendering private property to the Soviet state can be gauged by the fact that in only two months—July and August 1949—the number of Moldovan properties turned into Soviet kolkhozes more than doubled, growing from 32.2 percent at the end of June 1949 to 72.3 percent at the end of August 1949. By deportations as well as other means, the dramatic process leading to the eradication of private property in Moldova’s countryside was completed by the end of 1950, when 97 percent of the Soviet republic’s private farmlands had been wiped out and merged into state-controlled collective farms.

The last stroke of that second wave of deportations enforced secret Decree No. 00193 of the Soviet Union’s State Security Ministry, issued in Moscow on 5 March 1951. It was carried out between 4:00 A.M. and 8:00 P.M. on 1 April 1951, when, under the code name "Sever" (Operation North), 2,617 persons—808 men, 967 women, and 842 children—making up 723 families of Jehovah’s Witnesses—were deported under military escort to Siberia.

Under the less brutal policies of "planned transfer of labor," a third wave of deportations began in 1955, with emphasis on the transfer of thousands of Moldova peasants to the trans-Ural regions of the USSR’s Russian Federation, where they were lured to move by offers of lesser taxation and other forms of material assistance. Moldovan settlements bearing such names as Teiul, Zâmbreni, Bălcineşti, Logăneşti, Basarabia Nouă, are to be found, for instance, north of Vladivostok in the Ussury valley. Other Moldovan settlements can be found in the region of Tomsk, in the vicinity of Irkutsk, and in the Arkhangelsk region.

Definitive figures are hard to assess, but the number of Moldovan deportees throughout the years of Soviet rule is considered to be around half a million. According to the 1958 edition of the British Encyclopedia (volume 15, p. 662), it was estimated that by mid-1955, the Soviet authorities had deported about 500,000 people from the MSSR. A corroborating indication is the fact that in 1979, according to Soviet statistics, there were 415,371 Moldovans living in Ukraine, over 100,000 in various parts of the USSR’s Russian Federation, including Siberia and the Russia’s Far East, over 33,000 in Soviet Central Asia and other distant places of the USSR.

Related article: History of Moldova

Society

“They are not needy, but they need help”. How Moldovan volunteers try to create a safe environment for the Ukrainian refugees

At the Government’s ground floor, the phones ring constantly, the laptop screens never reach standby. In one corner of the room there is a logistics planning meeting, someone has a call on Zoom with partners and donors, someone else finally managed to take a cookie and make some coffee. Everyone is exhausted and have sleepy red eyes, but the volunteers still have a lot of energy and dedication to help in creating a safe place for the Ukrainian refugees.

“It’s like a continuous bustle just so you won’t read the news. You get home sometimes and you don’t have time for news, and that somehow helps. It’s a kind of solidarity and mutual support,” says Vlada Ciobanu, volunteer responsible for communication and fundraising.

The volunteers group was formed from the very first day of war. A Facebook page was created, where all types of messages immediately started to flow: “I offer accommodation”, “I want to help”, “I want to get involved”, “Where can I bring the products?”, “I have a car and I can go to the customs”. Soon, the authorities also started asking for volunteers’ support. Now they all work together, coordinate activities and try to find solutions to the most difficult problems.

Is accommodation needed for 10, 200 or 800 people? Do you need transportation to the customs? Does anyone want to deliver 3 tons of apples and does not know where? Do you need medicine or mobile toilets? All these questions require prompt answers and actions. Blankets, sheets, diapers, hygiene products, food, clothes – people bring everything, and someone needs to quickly find ways of delivering them to those who need them.

Sometimes this collaboration is difficult, involves a lot of bureaucracy, and it can be difficult to get answers on time. “Republic of Moldova has never faced such a large influx of refugees and, probably because nobody thought this could happen, a mechanism of this kind of crisis has not been developed. Due to the absence of such a mechanism that the state should have created, we, the volunteers, intervened and tried to help in a practical way for the spontaneous and on the sport solutions of the problems,” mentions Ecaterina Luțișina, volunteer responsible for the refugees’ accommodation.

Ana Maria Popa, one of the founders of the group “Help Ukrainians in Moldova/SOS Українці Молдовa” says that the toughest thing is to find time and have a clear mind in managing different procedures, although things still happen somehow naturally. Everyone is ready to intervene and help, to take on more responsibilities and to act immediately when needed. The biggest challenges arise when it is necessary to accommodate large families, people with special needs, for which alternative solutions must be identified.

Goods and donations

The volunteers try to cope with the high flow of requests for both accommodation and products of all kinds. “It came to me as a shock and a panic when I found out that both mothers who are now in Ukraine, as well as those who found refuge in our country are losing their milk because of stress. We are trying to fill an enormous need for milk powder, for which the demand is high and the stocks are decreasing”, says Steliana, the volunteer responsible for the distribution of goods from the donation centers.

Several centers have been set up to collect donations in all regions of Chisinau, and volunteers are redirecting the goods to where the refugees are. A system for processing and monitoring donations has already been established, while the volunteer drivers take over the order only according to a unique code.

Volunteers from the collection centers also do the inventory – the donated goods and the distributed goods. The rest is transported to Vatra deposit, from where it is distributed to the placement centers where more than 50 refugees are housed.

When they want to donate goods, but they don’t know what would be needed, people are urged to put themselves in the position of refugees and ask themselves what would they need most if they wake up overnight and have to hurriedly pack their bags and run away. Steliana wants to emphasise that “these people are not needy, but these people need help. They did not choose to end up in this situation.”

Furthermore, the volunteer Cristina Sîrbu seeks to identify producers and negotiate prices for products needed by refugees, thus mediating the procurement process for NGOs with which she collaborates, such as Caritas, World Children’s Fund, Polish Solidarity Fund, Lifting hands, Peace Corps and others.

One of the challenges she is facing now is the identifying a mattress manufacturer in the West, because the Moldovan mattress manufacturer that has been helping so far no longer has polyurethane, a raw material usually imported from Russia and Ukraine.

Cristina also needs to find solutions for the needs of the volunteer groups – phones, laptops, gsm connection and internet for a good carrying out of activities.

Hate messages

The most difficult thing for the communication team is to manage the hate messages on the social networks, which started to appear more often. “Even if there is some sort of dissatisfaction from the Ukrainian refugees and those who offer help, we live now in a very diverse society, there are different kind of people, and we act very differently under stress,” said Vlada Ciobanu.

Translation by Cătălina Bîrsanu

Important

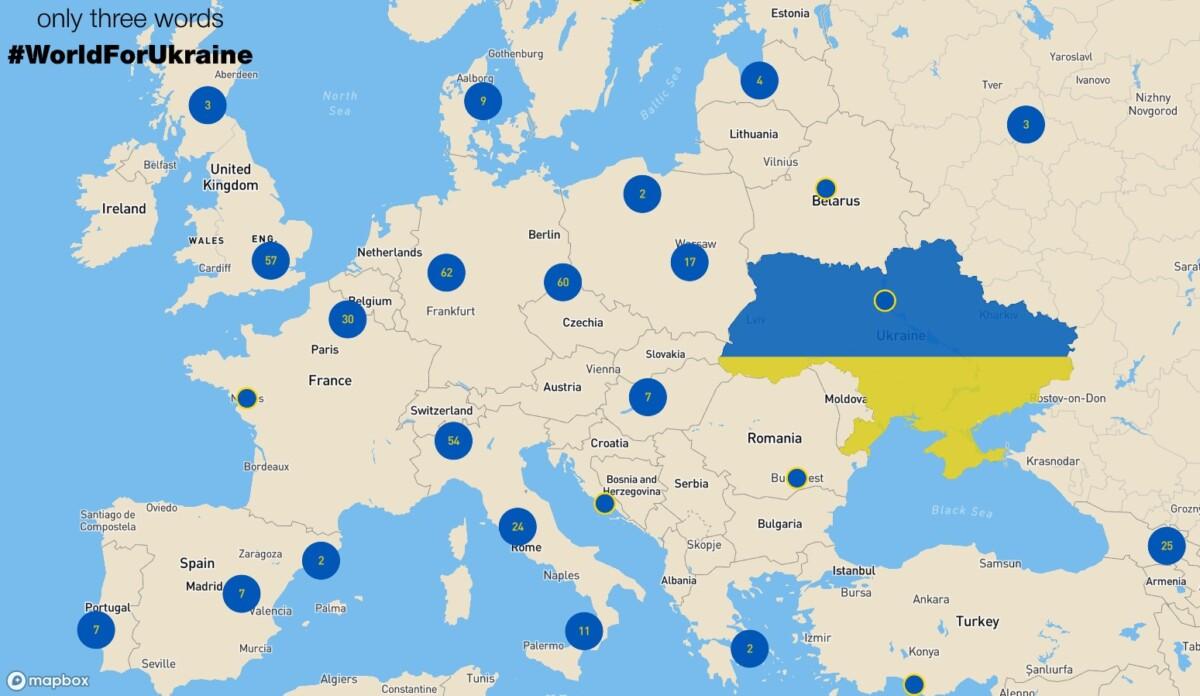

#WorldForUkraine – a map that shows the magnitude of the world’s actions against Russian aggression

The international community and volunteers from all over te world have launched #WorldForUkraine as a platform that shows the magnitude of the world’s actions against the Russian aggression. In a digital world – it is an interactive map of public support of Ukrainians under the hashtag #WorldForUkraine – rallies, flash mobs, protests around the world. In the physical dimension – it is your opportunity to take to the streets and declare: “No to Putin’s aggression, no to war.”

„Today, along with the political and military support, emotional connection with the civilized world and truthful information are extremely important for Ukraine. The power to do it is in your hands. Join the #WorldForUkraine project and contribute to the victorious battle against the bloodshed inflicted on Ukraine by the aggression of the Russian Federation”, says the „about the project” section of the platform.

Go to the streets — Tell people — Connect and Unite — Become POWERFUL

Volunteers have launched #WorldForUkraine as a platform that shows the magnitude of the world’s actions against Russian aggression. In digital world – it is an INTERACTIVE MAP of public support of Ukrainians worldforukraine.net under the hashtag #WorldForUkraine – rallies, flash mobs, protests around the world. In the physical dimension – it is your opportunity to take to the streets and declare: “No to Putin’s aggression, no to war.” There you may find information about past and future rallies in your city in support of Ukraine. This is a permanent platform for Ukrainian diaspora and people all over the world concerned about the situation in Ukraine.

So here’s a couple of things you could do yourself to help:

* if there is a political rally in your city, then participate in it and write about it on social media with geolocation and the hashtag #WorldForUkraine

* if there are no rallies nearby, organize one in support of Ukraine yourself, write about it on social media with geolocation adding the hashtag #WorldForUkraine

The map will add information about gathering by #WorldForUkraine AUTOMATICALLY

Your voice now stronger THAN ever

All rallies are already here: https://worldforukraine.net

Important

How is Moldova managing the big influx of Ukrainian refugees? The authorities’ plan, explained

From 24th to 28th of February, 71 359 Ukrainian citizens entered the territory of Republic of Moldova. 33 173 of them left the country. As of this moment, there are 38 186 Ukrainian citizens in Moldova, who have arrived over the past 100 hours.

The Moldovan people and authorities have organized themselves quickly from the first day of war between Russia and Ukraine. However, in the event of a prolonged armed conflict and a continuous influx of Ukrainian refugees, the efforts and donations need to be efficiently managed. Thus, we inquired about Moldova’s long-term plan and the state’s capacity to receive, host, and treat a bigger number of refugees.

On February 26th, the Ministry of Labor and Social Protection of Moldova approved the Regulation of organization and functioning of the temporary Placement Center for refugees and the staffing and expenditure rules. According to the Regulation, the Centers will have the capacity of temporary hosting and feeding at least 20 persons, for a maximum of 3 months, with the possibility of extending this period. The Centers will also offer legal, social, psychological, and primary medical consultations to the refugees. The Center’s activity will be financed from budget allocations, under Article 19 of Provision no. 1 of the Exceptional Situations Commission from February 24th, 2022, and from other sources of funding that do not contravene applicable law.

The Ministry of Inner Affairs and the Government of Moldova facilitated the organization of the volunteers’ group “Moldova for Peace”. Its purpose is to receive, offer assistance and accommodation to the Ukrainian refugees. The group is still working on creating a structure, registering and contacting volunteers, etc. It does not activate under a legal umbrella.

Lilia Nenescu, one of the “Moldova for Peace” volunteers, said that the group consists of over 20 people. Other 1700 registered to volunteer by filling in this form, which is still available. The group consists of several departments:

The volunteers’ department. Its members act as fixers: they’re responsible for connecting the people in need of assistance with the appropriate department. Some of the volunteers are located in the customs points. “The Ministry of Inner Affairs sends us every day the list of the customs points where our assistance is needed, and we mobilize the volunteers”, says Lilia Nenescu.

The Goods Department manages all the goods donated by the Moldavian citizens. The donations are separated into categories: non-perishable foods and non-food supplies. The volunteers of this department sort the goods into packages to be distributed.

The Government intends to collect all the donations in four locations. The National Agency for Food Safety and the National Agency for Public Health will ensure mechanisms to confirm that all the deposited goods comply with safety and quality regulations.

The Service Department operates in 4 directions and needs the volunteer involvement of specialists in psychology, legal assistance (the majority of the refugees only have Ukrainian ID and birth certificates of their children); medical assistance; translation (a part of the refugees are not Ukrainian citizens).

According to Elena Mudrîi, the spokesperson of the Ministry of Health, so far there is no data about the number of Covid-19 positive refugees. She only mentioned two cases that needed outpatient medical assistance: a pregnant woman and the mother of a 4-day-old child.

The Accommodation Department. The volunteers are waiting for the centralized and updated information from the Ministry of Labor about the institutions offering accommodation, besides the houses offered by individuals.

The Transport Department consists of drivers organized in groups. They receive notifications about the number of people who need transportation from the customs points to the asylum centers for refugees.

The municipal authorities of Chișinău announced that the Ukrainian children refugees from the capital city will be enrolled in educational institutions. The authorities also intend to create Day-Care Centers for children, where they will be engaged in educational activities and will receive psychological assistance. Besides, the refugees from the municipal temporary accommodation centers receive individual and group counseling.

In addition to this effort, a group of volunteers consisting of Ana Gurău, Ana Popapa, and Andrei Lutenco developed, with the help of Cristian Coșneanu, the UArefugees platform, synchronized with the responses from this form. On the first day, 943 people offered their help using the form, and 110 people asked for help. According to Anna Gurău, the volunteers communicate with the Government in order to update the platform with the missing data.

Translation from Romanian by Natalia Graur