Tourism

“Along lesser traveled roads”- trip to Moldova, part one

Darius Roby is a travel writer, translator, and an editor for Cluj.com, a city portal with information pertaining to life and tourism in Cluj-Napoca. He can be reached at [email protected]

He shared with us his journal of the trip to Moldova.

There is something very romantic about the trip from Cluj-Napoca to Chisinau. It is not the easiest thing to explain, especially because I cannot quite figure it out myself. Perhaps it is the geographer in me finding the transition from mountains to the slightly rolling steppes to be fascinating. Perhaps the rural Mississippi boy in me smiles at the thought of crossing the river Pruth just as the Sun begins to peek over the horizon and you can see people slowly making their way to begin the day’s work in the wheat fields. Perhaps it is even the ethnographer in me, crossing that invisible cultural boundary from one world to another – from the European Union into the former Soviet Union. Whatever the reason may be, it is one that I have made on a few occasions in the past and one that I recently got to again enjoy.

Cities in Eastern Europe are not as well connected as those in the West are. A trip from Paris to Marseille is as simple as a three hour train ride. Milan can be reached from Paris in less than an hour on an EasyJet flight. Cluj to Chisinau? You are looking at a 12 hour overnight bus ride. Despite the length of time, such trips have a way of allowing you to see vast stretches of land, a smattering of various accents as people go on and leave the bus in various cities, and an opportunity for a few very uncomfortable naps. It almost takes one back into a time and place where the world was not as interconnected as it is today. One can feel almost as if he is Verne’s Phileas Fogg, exploring a world that is known to scholarship, but still remote enough to enchant the soul of a foreigner.

Such as it is, one Friday afternoon I finished work, hastily stuffed my backpack with a few essentials, and headed to the bus station in Cluj-Napoca. Despite a departure time of 6pm, it would be nearly 7 before we found open road due to the Friday evening end of the work week traffic jams that are the same all over the world. The rolling hills of Transylvania soon became the heavily forested Carpathian mountains and eventually so on into the sub-Carpathian rolling hills of the badly mis-named Moldovan “Plateau.”

We reached the border around 3 am, at Albița. The passport check went without a hitch and we crossed the Pruth River into Moldova at Leușeni. Again, the passport check was a breeze and I took the opportunity to convert some of my money into Moldovan lei. I was not very certain how much I would need but if the hosts of the Ukrainian television show “Oryol i Reshka” can survive in former Soviet cities with $100 US for an entire weekend then I imagined that I would be fine. I am a big fan of the Eurolines bus that handles the Cluj – Chisinau route for the simple reason that they are very good at timing the border crossing with the rise of the early June Sun. It is quite a spectacle to have the sunrise welcome you into Moldova. One of the first things that drew me to pull back the window curtains was the sight of men and women walking slowly to the wheat fields in the twilight to engage in the art of agriculture. It is a dance that has gone on for thousands of years and I took note that early June is usually the time of year in which people often celebrate warm weather, long summer days, and defeat of winter. Having spent the past five years living in Romania, I have come to understand very well that the final end of cold days is always worth celebrating.

A couple of bumpy hours later the bus arrived in Chisinau. The city was very quiet and eerie during the morning and I took note that a majority of advertisement billboards were for candidates participating in upcoming elections. For every candidate that promised Moldovans prosperity in Europe, there was one that promised trade relations and good pensions under the aegis of Russia. I got off the bus on Ștefan cel Mare și Sfînt Boulevard and took in my bearings. Taxis can sometimes be a bit tricky to find in Chisinau but I was lucky to find one at the bus stop and from there made my way to the Gara de Nord. To the best of my knowledge, Chisinau has three bus stations – North, South, and Central. The Gara de Nord is from where one can find buses to northern cities in Moldova as well as buses to Ukraine, Belarus, and Russia. At the Gara de Sud one can find buses to southern cities in Moldova as well as to Romania. I have to make a mental note to one day ask someone to where one can go to from the central bus station.

I lazily walked into the bus station with the idea of grabbing a bite before finding a bus to Soroca. As the saying goes, even the best laid plans can often go astray. I was immediately set upon by a bus driver who eagerly asked me to where I was going. “To Soroca” I replied, only to be pointed to a minibus that was already backing up to leave the bus station. I smiled ironically at my good fortune, ran to stop the minibus, managed to get on, and found a seat in the back. True to Soviet style, I asked the driver the price and passed my money ahead to the next passenger, who subsequently passed it on to the next passenger until it reached the driver. Then, my change returned the same way. Like a cold cup of kvas, it is one of those little things that endears me to this part of the world.

We began heading north and I noticed a big difference from the last time I visited Moldova – the road was newly renovated and in excellent condition. In the great game of the US and Russia competing for the hearts and political souls of Georgia, Ukraine, and Moldova, an American organization has recently given Moldova money in order to modernize and renovate the Chisinau – Soroca highway. What I had fully expected to be a long bumpy ride ended up becoming a shorter and more comfortable trip with signposts every 10 kilometers reminding drivers that the money of the American people had paid for their comfortable experience.

Moldova is a very beautiful country to see during the late spring. The land is very green and full of life. The geography is in some places composed of the last vestiges of the rolling sub-Carpathian hills, while in other places you see the beginnings of the great Pontic steppe. Once upon a time the country was heavily forested and it was in these forests did people seek refuge in the face of invaders from the East such as the Polovtsi and the Tatars. Along the road I see place names that are associated with historical significance – Perescina, the former capital of an early medieval Slavic tribe, Orheiul Veche – part of Ștefan cel Mare’s defense system, Ciocîlteni – where I ate racitura for the first time in my life. My love of history is what was taking me to Soroca this day; to see the newly renovated fortress that sits proudly next to the Dniester River.

Due to the nature of the road I ended up arriving in Soroca a bit earlier than I expected. Upon arrival I thanked the driver, wished him good health, and began walking from the bus station. Immediately I was waylaid by a middle aged Gypsy man who having noticed my coarse curly hair took off his hat to reveal his own similarly curled hair to me. He smiled and asked me where I am from. He was very surprised to hear that an American would ever visit Soroca. As he spoke, I began to ponder to myself where in his family tree could he have come about such hair. That is one of the most interesting things about Eastern Europe to me – being the gateway between East and West has created some very interesting genetic and cultural features among people. I smiled to myself wondering what Moldovan people were probably thinking about my American accented Russian and Romanian.

It was only 10 am and the weather was already scorching hot, even for this Mississippi boy. As I saw a couple of school buses full of small children heading towards the direction of the fortress, I told myself that I could wait a while before seeing it myself and that I felt like relaxing a bit. I never travel with maps, mostly out of arrogance, and this time it came to bite me as I could not quite figure out where my hotel was. Luckily, Soroca is a small enough city to where it is easy to get directions, walk around, and I soon found the Hotel Central. It is in a lovely (as the name states – central) location and offers all the services that one could ask for in a hotel – including a terrace on a hot day. I checked in, set my backpack next to me, and drank a beer like an elephant at a watering hole on the savanna. Refreshed, and wiping the sweat from my brow, I began to reflect on how rewarding it is to travel, especially along lesser traveled roads, and to gain new perspectives on the world. I soon found myself engaged in conversation with an older man who inquired to why would I ever want to visit Moldova. I found my inner T.E. Lawrence and replied with a smile – “Because it is clean.”

Culture

The village of the first astronomer in the Republic of Moldova

Culture

Vîșcăuți, the Moldovan village where you feel like heaven

Reading Time: 9 minutesShe enters the house in a hurry and arranges the corner of the entrance mat. She leaves her purse and other items on the kitchen chair and starts washing the dishes. Then she goes to the second floor, changes the sheets on the beds, arranges the trinkets on the table, draws the curtains and opens the windows to aerate the room. From the window you can see the Nistru river, its banks covered with fresh vegetation. The woman sees to her tasks. She vacuums, she cleans the floors and starts all over again on the first floor.

Then she moves to the old house next door. Nobody was accommodated in this house yet, as everyone prefers “euro” repairs, as Lucia, the 52 years old administrator of the guest house, explains. But she doesn’t let the dust settle on the furniture and always has the rooms ready to accommodate guests.

The House of the Boyar is a guest house in the village of Vîșcăuți, Orhei, and can accommodate up to 8 persons. It is part of an eco-cultural touristic project “Bronze Half-moon” (“Semiluna de bronz”), which aims at attracting tourists in rural regions, offering them authentic experience, but it also promotes social entrepreneurship.

Besides involving the locals by creating jobs, the project also offers the opportunity and necessary support for the villagers to sell their products and services. Also, the profit is reinvested in the locality and its development. For example, now they work on developing a touristic trail through the forests of Vîșcăuți with all the necessary infrastructure, which will benefit the visitors of the village, as well as the locals.

Lucia quickly sweeps in the yard and takes out the trash. She managed to tidy up in just about two hours. A group of tourists just left and another one is coming. Lucia Frunză took off her apron and is ready to welcome the guests. “They come from Chișinău, they come from everywhere,” she says in a hurry.

Lucia remembers when she received a group of 18 people. At their request, she cooked them plăcinte, pot roast and mămăligă. But she decided to make them a surprise and prepared some mulled wine. “As a bonus. I have a special recipe. I add black pepper, sugar, lemon, oranges and a little vanilla. These give the wine such an arooomaaa.”

She is a very good cook. And one of her secrets is a special knife, which she carries with her from home to the guest house and back. It’s a cleaver with a wavy pattern blade, so when she cuts produce, it has jagged edges. When she makes soup, she cuts the potatoes, the carrots, the meat and the onion – she slices everything with it. Once she brought a bowl of soup to uncle Colea. “Oh, this soup with farfalle is so good, it’s like at a restaurant!,” recalls Lucia amused about the impression she made on the neighbor.

The meadow and the cave

Gheorghe and Ludmila Frunză live down the road from the guest house. When Lucia has too much on her plate, the old couple helps her out with cooking or with laundry. He is 74 years old, and she is 70. In summertime, the couple spends their second youth in Vîșcăuți. In winter, when it’s cold, they go back to Chișinău.

Gheorghe was born here, and he knows all the surroundings like his five fingers. He knows how to reach the Boyar’s Cave two ways: one is more difficult and the other one easier.

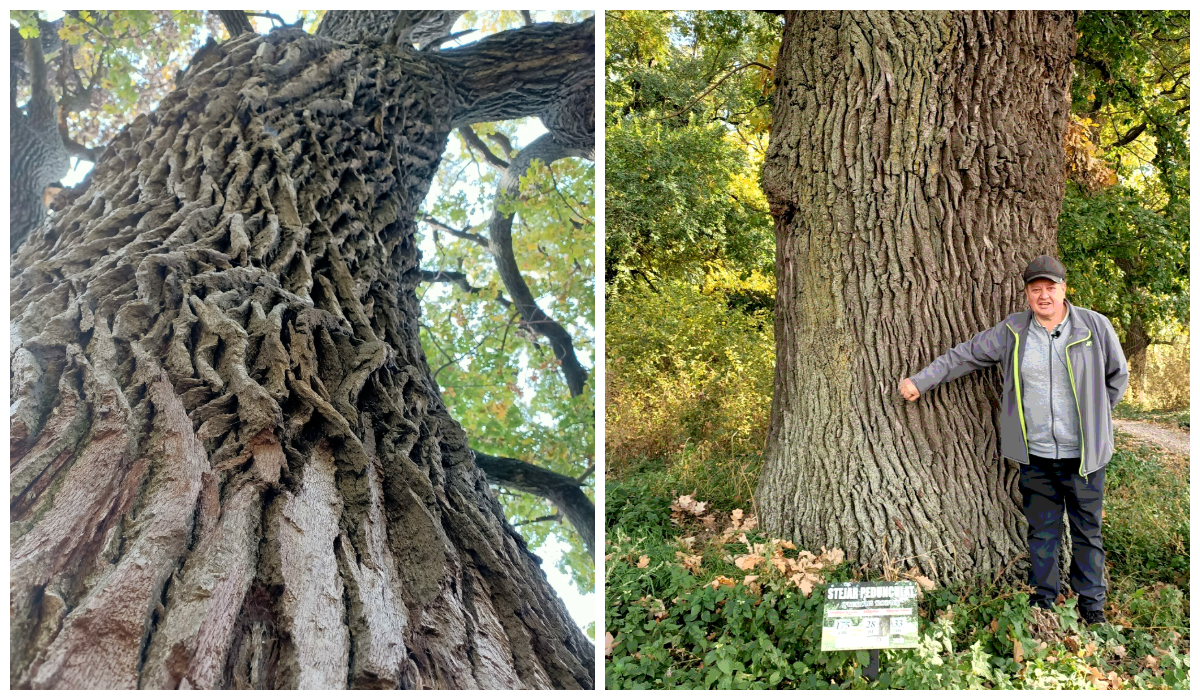

If you are in good shape and have the courage, you can reach the Boyar’s Cave through the ravine. But Gheorghe’s legs can’t keep up with this trail as he used to. The pathway to the cave goes between two rocky hills. You will step on the slippery rocks, washed by the cold water of the springs. You will climb the trees so thick, you can’t embrace with both hands, knocked down by the summer rain.

You will slowly advance towards the cave located up the hill, where you’ll see the Cornelian cherry dogwood full of hard-to-reach red berries, which local people pick for making compote. If you try and yell between the two rocky hills, your voice will not travel far. You will have no use of modern technologies, and your phone will only be good for taking pictures. Here you can breathe fresh cold air, while embraced by the silence dictated only by the murmur of the water.

Once you reach the cave, you need a lantern. On the walls you can see “V+M=LOVE”, but also hanging bats – almost embraced one next to another. There are three entrances to the cave and many labyrinths. No one knows exactly what are its measurements. There are some assumptions that it’s one kilometer long. But you can’t really reach its depths, because it collapsed a long time ago.

There are many legends about the origin of the cave. Gheorghe tells us that it used to be a quarry, tons of rock being extracted for the construction of churches.

Actually, according to archives, the cave was dug by the Sandino boyar around 1900 for storing wine barrels.

Locals say that during the two world wars, the cave was used as shelter for their grandparents and great-grandparents, and that they were guarded by the soldiers stationed in Vîșcăuți.

The old couple takes us on the river bank. “If you get on the boat and sail on the river, watching the forest… It’s such a beauty!,” Gheorghe tells us with excitement. He walks slowly and looks towards Nistru, watching the swans, the forest. “The air in Vîșcăuți almost makes you drunk,” he adds. He is followed by his wife Liuda and Daniel, a boy from the neighborhood.

They want to visit the three springs. It is said that the water of each of the springs has distinctive tastes. When they get to the place, they can see tourists’ traces: campfire ash, some pieces of paper. Tourists are not uncommon in these places. Gheorghe tells us that they come with their tents and spend a couple of days here fishing. He likes spending time with them. “All of them say that this is a nice quiet place”.

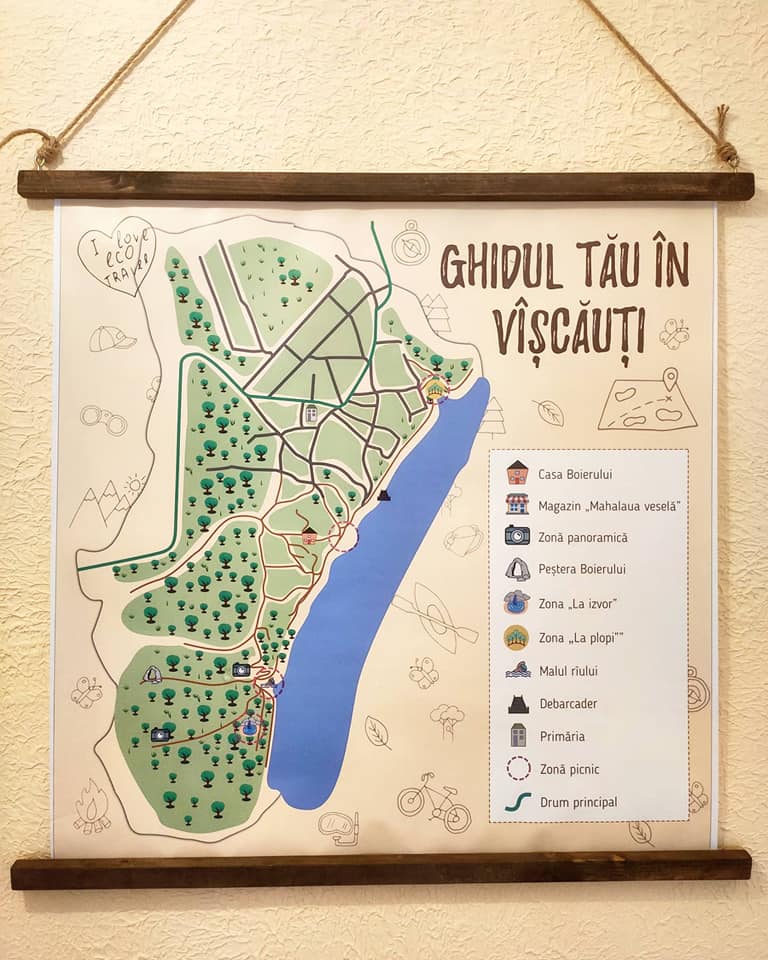

Map drawn for the tourists who visit the Boyar’s House

In Vîșcăuți you can rent a boat from the locals. You can also buy homemade bread, wine and free range chicken, fresh river fish, home grown vegetables. The village also has a beach, a picnic area, a wharf and a neighborhood called “The joyful neighborhood” due to the events organized here. From time to time, people gather here and cook fish soup or barbeque, they play some music, dance and party.

“The hill of Chirița” opens a view of Nistru river and the surrounding areas. “Now everything has dried-up… But when it’s green, the flowers there are wonderful!,” says Gheorghe.

“In Rață’s music video they showed the entire village. They filmed the forest and our meadow”, recalls Gheorghe. “There is also a song – My meadow. He sang it on TV many times,” adds Ludmila.

„Over the mountain, over the river – is my meadow,

Sometimes yearly, sometimes late – I take a walk there,

Over the mountain, over the river – flowers and roses,

Over the mountain, over the river – hidden memories.”

The lyrics to the song “My meadow”, sang by Moldovan singer Ion Rață, born in Vîșcăuți, where the music video was filmed.

Since the pandemic started, Ludmila and Gheorghe appreciate life in the village even more. “When the pandemic started, everyone was so agitated and scared. When we were in Chișinău, we would see all the ambulances and police cars throughout the entire city. But when we came here, it was like coming to heaven. When you get in the yard, you don’t need the mask any longer. We are peaceful here and we see to our chores. In Chișinău we didn’t have anything to do, except sitting on the benches outside. But here we exercise, we grow vegetables, fruits, we make canned food for winter,” Ludmila explains. She appreciates the tourists visiting the village, because the people have the opportunity to sell something to them. “They really don’t have a way to sell something in the village, no means to make a living.”

The luck and the happiness to be born at the river

Because the village is located on the banks of Nistru, the river is the one dictating the life in the region: it gives people water, it gives them food, but also leisure areas. Gheorghe remembers that especially during the soviet period he would visit his relatives on the other side of the river, in the village of Harmațca. They would barbeque under the willows near the river and then cross Nistru and continue their party under the willows of Vîșcăuți.

At the guest house, while stirring the pot roast, Lucia is humming a sad song. She is absorbed by the process and lets herself caught up in the moment:

Nistru, don’t drown me,

Nistru, don’t drown me,

Shai-rai-rai-ra, Shai-rai-rai-ra.

You don’t have the money to burry me,

You don’t have the money to burry me,

Shai-rai-rai-ra, Shai-rai-rai-ra.

“I woke up to this song. I woke up with my grandparents, with my parents, with the entire village singing it, and we learned it.” She grinds some cheese on a plate, and on another she puts some parmesan – so it’ll be tastier with the mămăliga. She puts some clay plates on the table and invites the guests.

“I am very proud to be born near the river,” says Lucia. She has happy memories of her childhood, when the winters were colder and the ice on the river could reach even 1 meter in depth. “Cars and tractors, even trucks with gas tanks would cross Nistru, driving towards the Transnistrian region,” she explains.

1 434 |

1 210 |

People live in VîșcăuțiSources: BNS, 2014 |

People live in HarmațcaSources: dubossary.ru, 2013 |

Even today, the bond between the two river banks is not lost. Lucia has relatives living in the village across the river, in Harmațca. “We have brothers and sisters, we have cousins, we are all related to each other. Because it’s a whole.”

Produced with the financial support of the European Union within the “Support to Confidence Building Measures” project, implemented by UNDP. The opinions expressed in this material do not necessarily reflect the official position of the EU or UNDP.

Economy

Romania and Moldova signed a partnership memorandum pledging to cooperate in promoting their wines

Reading Time: 2 minutesThe Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Romania (CCIR) and the National Office for Vine and Wine (NOVW) of the Republic of Moldova signed, last week, a memorandum of cooperation on organizing joint promotional activities in the markets of common interest, as the CCIR announced.

China, Japan or the USA are just some of the markets targeted by the Romanian and Moldovan institutions. The memorandum also involves advertising activities for wines from common indigenous varieties, promoting the oeno-tourist region, developing a tourist route in the two states, exchange of experience, study visits, and mutual support in identifying new export opportunities. “We are very confident that this collaboration between our organizations will lead to sustainable economic growth and a higher degree of well-being among Moldovans and Romanians,” claimed Deputy Secretary-General of CCIR, Bogdan Visan.

On the other hand, Director of the NOVW, Cristina Frolov, declared that no open competition with Romania is aimed at the governmental level of the Republic of Moldova. “This request for collaboration is a consequence of the partnership principle. Romania imports 10-12% of the wine it consumes, and we want to take more from this import quota. Every year, the Romanian market grows by approximately 2.8%, as it happened in 2020, and we are interested in taking a maximum share of this percentage of imported wines without entering into direct competition with the Romanian producer,” the Moldovan official said. She also mentioned that Moldova aims at increasing the market share of wine production by at least 50% compared to 2020, and the number of producers present on the Romanian market – by at least 40%.

Source: ccir.ro

**

According to the data of the Romanian National Trade Register Office, the total value of Romania-Moldova trade was 1.7 billion euros at the end of last year and over 805 million euros at the end of May 2021. In July 2021, there were 6 522 companies from the Republic of Moldova in Romania, with a total capital value of 45.9 million euros.

The data of Moldova’s National Office of Vine and Wine showed that, in the first 7 months of 2021, the total quantity of bottled wine was about 27 million litres (registering an increase of 10% as compared to the same period last year), with a value of more than one billion lei, which is 32% more than the same period last year. Moldovan wines were awarded 956 medals at 32 international competitions in 2020.

Photo: ccir.ro