Tourism

Movilă Măgura- A Monument to the Passage of Time

Darius Roby is a travel writer, translator, and an editor for Cluj.com, a city portal with information pertaining to life and tourism in Cluj-Napoca. He is also a contributor to Ukraine Today and is a member of the Hakluyt Society.

In western Moldova, the borders of the Fălești, Ungheni, and Sîngerei districts meet at a place that is most spectacular. The topography is hilly, some of the most dramatic and highest in the country. The poorly maintained roads provide a sense of wild elation as our car speeds over the steep hills and valleys, almost as if one is on a roller coaster. After passing the village of Sărata Veche, my guide, Maria, smiled and beckoned me to look towards the horizon, where I beheld a large hill. There, in the early evening light, one could make out the outline of a large mound crowning the summit in the distance. Thus we had arrived at the Măgura Hill. It is one of the tallest in Moldova, rising to a height of 1200 feet.

Despite our proximity, we still had a long way to go to reach the mound itself. Reaching the village of Sărata Noua, we left the main road and passed along winding rural roads through Ciolacu Nou and Ciolacu Vechi, often having to make way for passing ducks, turkeys, and geese. The road was, in many places, little more than a trail carved by cars on a dirt path. Had the weather been more wet that day, the climb would have been impossible to traverse by car. After passing through Ciolacu Vechi, quiet woodland greeted us to our left as we continued to climb until we finally reached the plateaued summit, pleased with our progress.

Upon arrival, I immediately wrapped my jacket tightly around me, shocked by how heavily the wind blows there. Taking an appraisal at our surroundings, it was easy to understand why. The Măgura Hill towers over the surrounding region. From the summit, one could enjoy a panorama of corn fields, little villages, and forests stretching far towards the west, where the early autumn sun was beginning to set over the river Prut. Towards the eastern slope, there is a tiny compound where a lonely monk lives. Hence derives the name măgura, which refers to a large and isolated hill in the Romanian language. The name has also inspired the names of numerous villages that can be found around the hill – Măgurele, Măgura, Măgura Nouă, and Slobozia Măgura.

Unlike the mounds at the previously mentioned Sută de Movile, the Movilă Măgura is not a natural formation. It is a true tumulus, or kurgan, as monuments of the type are referred to as in Eastern European archaeology. It stands nearly 50 feet tall, and is crowned with a stone cross that has been plated with reflective stainless steel. As a result, the cross can be seen from a great distance on clear and sunny days. In regards to who may have built the structure, no one really knows. During the 1990s, there were archaeological excavations undertaken at the tumulus which discovered a settlement and pottery fragments of the Cucuteni culture. Taking into consideration that the Cucuteni culture existed from 6000 to 3500 BC, could the tumulus really be much older than the first pyramids in Egypt?

However, we know next to nothing concerning Cucuteni burials rites. As very few Cucuteni bones have ever been discovered, there are conjectures that range in explanation from the cremation of the deceased to simply scattering their bones far away from settlements. Moreover, the shape and nature of the Movilă Măgura points towards nomadic steppe cultures far more than the relatively peaceful, settled Cucuteni civilization. Perhaps the tumulus dates from the Yamna culture, the original kurgan culture, which spread from southern Ukraine and Russia into Eastern Europe – conquering the Cucuteni culture at the end of the Neolithic age. It could also feasibly have been built by their later cultural successors – the Cimmerians, Scythians, or Sarmatians. Due to the commanding position of the Măgura tumulus, it be unsurprising if we were beholding the tomb of a great warrior or king.

Geography also comes into question here. The hills and forests of west-central Moldova hardly seem accommodating towards the culture and lifestyle of nomadic hordes. Why would they bury their dead in such a location? As with the Sută de Movile, perhaps geology can tell us more. Maria explained to me that studies have been done regarding the soil in Fălești district that have concluded that the region may have once been a treeless steppe. According to this theory, the grassy steppe eventually retreated towards southern Moldova and the shores of the Black Sea with the passage of time. As a result, the environment may have supported the type of nomadic cultures that would have produced the Măgura tumulus. Tanya, the archaeologist among us, suggested that the hill may have also served as a lookout point for the surrounding region, where if the alarm were to be raised, it could be viewed over a great distance. I have indeed heard rumor before of other tumuli being used for such a purpose during the times of the Moldovan principality.

Whatever its origin, the tumulus has maintained a special place in the souls of the locals from the surrounding villages throughout the centuries. As late as the 1930s, it was considered sacred and often played host to religious rites and traditions. The cross that sits at the top of the tumulus is not the original, but rather a replacement for one that stood there during the interbellum period. When the Soviets conquered Moldova, the original cross was taken down, buried, and was replaced by an observatory. After Moldova’s independence, the present cross was raised and since then – the area has again become a place for gathering and merrymaking among the local villagers.

I do not know if the all the questions concerning the Măgura tumulus will ever be solved. There is evidence of illegal archaeology and grave robbing that have taken place at the mound, so if there are any Scythian treasures to be discovered there – they may have already been found and removed centuries ago. If there are kings or warriors there, then future excavations will be able to tell us more. At the least, it is a most beautiful and majestic sight. It is a symbol of the passage of time, the light from its cross remaining visible long after descending along the winding road, as the sun set towards our backs and we headed into the gathering dusk back towards Chișinău, and a well deserved glass of wine.

The trip was organized with the help of Maria Axenti from YG Moldova.

Maria Axenti is an anthropologist at Institute of Cultural Heritage of the Academy of Sciences of Moldova as well as the co-founder of YG Moldova, an organization dedicated to promoting the culture, people, and natural beauty of Moldova. To learn more about her work and for information concerning guided tours, visit YGmoldova.com.

Culture

The village of the first astronomer in the Republic of Moldova

Culture

Vîșcăuți, the Moldovan village where you feel like heaven

Reading Time: 9 minutesShe enters the house in a hurry and arranges the corner of the entrance mat. She leaves her purse and other items on the kitchen chair and starts washing the dishes. Then she goes to the second floor, changes the sheets on the beds, arranges the trinkets on the table, draws the curtains and opens the windows to aerate the room. From the window you can see the Nistru river, its banks covered with fresh vegetation. The woman sees to her tasks. She vacuums, she cleans the floors and starts all over again on the first floor.

Then she moves to the old house next door. Nobody was accommodated in this house yet, as everyone prefers “euro” repairs, as Lucia, the 52 years old administrator of the guest house, explains. But she doesn’t let the dust settle on the furniture and always has the rooms ready to accommodate guests.

The House of the Boyar is a guest house in the village of Vîșcăuți, Orhei, and can accommodate up to 8 persons. It is part of an eco-cultural touristic project “Bronze Half-moon” (“Semiluna de bronz”), which aims at attracting tourists in rural regions, offering them authentic experience, but it also promotes social entrepreneurship.

Besides involving the locals by creating jobs, the project also offers the opportunity and necessary support for the villagers to sell their products and services. Also, the profit is reinvested in the locality and its development. For example, now they work on developing a touristic trail through the forests of Vîșcăuți with all the necessary infrastructure, which will benefit the visitors of the village, as well as the locals.

Lucia quickly sweeps in the yard and takes out the trash. She managed to tidy up in just about two hours. A group of tourists just left and another one is coming. Lucia Frunză took off her apron and is ready to welcome the guests. “They come from Chișinău, they come from everywhere,” she says in a hurry.

Lucia remembers when she received a group of 18 people. At their request, she cooked them plăcinte, pot roast and mămăligă. But she decided to make them a surprise and prepared some mulled wine. “As a bonus. I have a special recipe. I add black pepper, sugar, lemon, oranges and a little vanilla. These give the wine such an arooomaaa.”

She is a very good cook. And one of her secrets is a special knife, which she carries with her from home to the guest house and back. It’s a cleaver with a wavy pattern blade, so when she cuts produce, it has jagged edges. When she makes soup, she cuts the potatoes, the carrots, the meat and the onion – she slices everything with it. Once she brought a bowl of soup to uncle Colea. “Oh, this soup with farfalle is so good, it’s like at a restaurant!,” recalls Lucia amused about the impression she made on the neighbor.

The meadow and the cave

Gheorghe and Ludmila Frunză live down the road from the guest house. When Lucia has too much on her plate, the old couple helps her out with cooking or with laundry. He is 74 years old, and she is 70. In summertime, the couple spends their second youth in Vîșcăuți. In winter, when it’s cold, they go back to Chișinău.

Gheorghe was born here, and he knows all the surroundings like his five fingers. He knows how to reach the Boyar’s Cave two ways: one is more difficult and the other one easier.

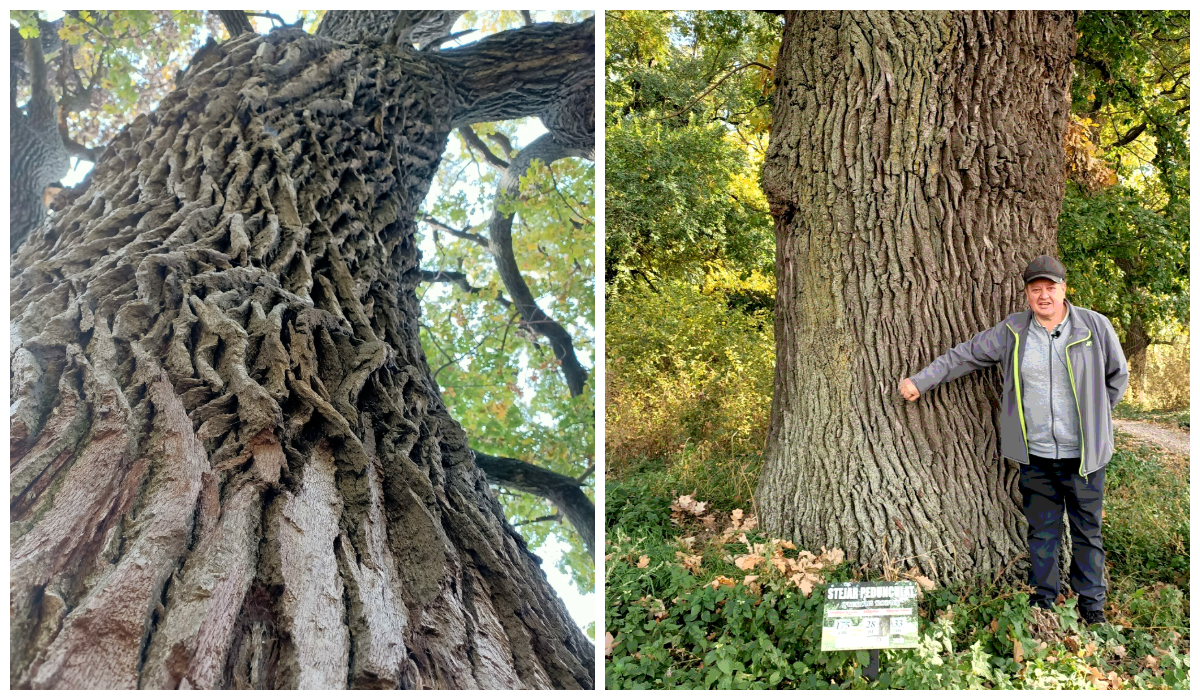

If you are in good shape and have the courage, you can reach the Boyar’s Cave through the ravine. But Gheorghe’s legs can’t keep up with this trail as he used to. The pathway to the cave goes between two rocky hills. You will step on the slippery rocks, washed by the cold water of the springs. You will climb the trees so thick, you can’t embrace with both hands, knocked down by the summer rain.

You will slowly advance towards the cave located up the hill, where you’ll see the Cornelian cherry dogwood full of hard-to-reach red berries, which local people pick for making compote. If you try and yell between the two rocky hills, your voice will not travel far. You will have no use of modern technologies, and your phone will only be good for taking pictures. Here you can breathe fresh cold air, while embraced by the silence dictated only by the murmur of the water.

Once you reach the cave, you need a lantern. On the walls you can see “V+M=LOVE”, but also hanging bats – almost embraced one next to another. There are three entrances to the cave and many labyrinths. No one knows exactly what are its measurements. There are some assumptions that it’s one kilometer long. But you can’t really reach its depths, because it collapsed a long time ago.

There are many legends about the origin of the cave. Gheorghe tells us that it used to be a quarry, tons of rock being extracted for the construction of churches.

Actually, according to archives, the cave was dug by the Sandino boyar around 1900 for storing wine barrels.

Locals say that during the two world wars, the cave was used as shelter for their grandparents and great-grandparents, and that they were guarded by the soldiers stationed in Vîșcăuți.

The old couple takes us on the river bank. “If you get on the boat and sail on the river, watching the forest… It’s such a beauty!,” Gheorghe tells us with excitement. He walks slowly and looks towards Nistru, watching the swans, the forest. “The air in Vîșcăuți almost makes you drunk,” he adds. He is followed by his wife Liuda and Daniel, a boy from the neighborhood.

They want to visit the three springs. It is said that the water of each of the springs has distinctive tastes. When they get to the place, they can see tourists’ traces: campfire ash, some pieces of paper. Tourists are not uncommon in these places. Gheorghe tells us that they come with their tents and spend a couple of days here fishing. He likes spending time with them. “All of them say that this is a nice quiet place”.

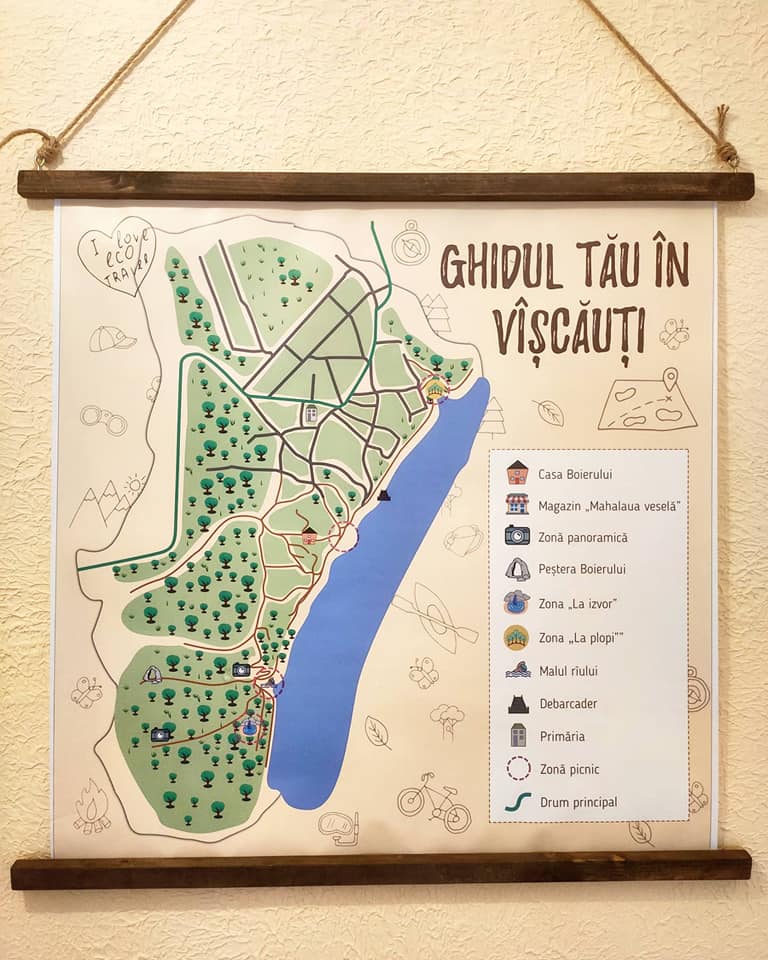

Map drawn for the tourists who visit the Boyar’s House

In Vîșcăuți you can rent a boat from the locals. You can also buy homemade bread, wine and free range chicken, fresh river fish, home grown vegetables. The village also has a beach, a picnic area, a wharf and a neighborhood called “The joyful neighborhood” due to the events organized here. From time to time, people gather here and cook fish soup or barbeque, they play some music, dance and party.

“The hill of Chirița” opens a view of Nistru river and the surrounding areas. “Now everything has dried-up… But when it’s green, the flowers there are wonderful!,” says Gheorghe.

“In Rață’s music video they showed the entire village. They filmed the forest and our meadow”, recalls Gheorghe. “There is also a song – My meadow. He sang it on TV many times,” adds Ludmila.

„Over the mountain, over the river – is my meadow,

Sometimes yearly, sometimes late – I take a walk there,

Over the mountain, over the river – flowers and roses,

Over the mountain, over the river – hidden memories.”

The lyrics to the song “My meadow”, sang by Moldovan singer Ion Rață, born in Vîșcăuți, where the music video was filmed.

Since the pandemic started, Ludmila and Gheorghe appreciate life in the village even more. “When the pandemic started, everyone was so agitated and scared. When we were in Chișinău, we would see all the ambulances and police cars throughout the entire city. But when we came here, it was like coming to heaven. When you get in the yard, you don’t need the mask any longer. We are peaceful here and we see to our chores. In Chișinău we didn’t have anything to do, except sitting on the benches outside. But here we exercise, we grow vegetables, fruits, we make canned food for winter,” Ludmila explains. She appreciates the tourists visiting the village, because the people have the opportunity to sell something to them. “They really don’t have a way to sell something in the village, no means to make a living.”

The luck and the happiness to be born at the river

Because the village is located on the banks of Nistru, the river is the one dictating the life in the region: it gives people water, it gives them food, but also leisure areas. Gheorghe remembers that especially during the soviet period he would visit his relatives on the other side of the river, in the village of Harmațca. They would barbeque under the willows near the river and then cross Nistru and continue their party under the willows of Vîșcăuți.

At the guest house, while stirring the pot roast, Lucia is humming a sad song. She is absorbed by the process and lets herself caught up in the moment:

Nistru, don’t drown me,

Nistru, don’t drown me,

Shai-rai-rai-ra, Shai-rai-rai-ra.

You don’t have the money to burry me,

You don’t have the money to burry me,

Shai-rai-rai-ra, Shai-rai-rai-ra.

“I woke up to this song. I woke up with my grandparents, with my parents, with the entire village singing it, and we learned it.” She grinds some cheese on a plate, and on another she puts some parmesan – so it’ll be tastier with the mămăliga. She puts some clay plates on the table and invites the guests.

“I am very proud to be born near the river,” says Lucia. She has happy memories of her childhood, when the winters were colder and the ice on the river could reach even 1 meter in depth. “Cars and tractors, even trucks with gas tanks would cross Nistru, driving towards the Transnistrian region,” she explains.

1 434 |

1 210 |

People live in VîșcăuțiSources: BNS, 2014 |

People live in HarmațcaSources: dubossary.ru, 2013 |

Even today, the bond between the two river banks is not lost. Lucia has relatives living in the village across the river, in Harmațca. “We have brothers and sisters, we have cousins, we are all related to each other. Because it’s a whole.”

Produced with the financial support of the European Union within the “Support to Confidence Building Measures” project, implemented by UNDP. The opinions expressed in this material do not necessarily reflect the official position of the EU or UNDP.

Economy

Romania and Moldova signed a partnership memorandum pledging to cooperate in promoting their wines

Reading Time: 2 minutesThe Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Romania (CCIR) and the National Office for Vine and Wine (NOVW) of the Republic of Moldova signed, last week, a memorandum of cooperation on organizing joint promotional activities in the markets of common interest, as the CCIR announced.

China, Japan or the USA are just some of the markets targeted by the Romanian and Moldovan institutions. The memorandum also involves advertising activities for wines from common indigenous varieties, promoting the oeno-tourist region, developing a tourist route in the two states, exchange of experience, study visits, and mutual support in identifying new export opportunities. “We are very confident that this collaboration between our organizations will lead to sustainable economic growth and a higher degree of well-being among Moldovans and Romanians,” claimed Deputy Secretary-General of CCIR, Bogdan Visan.

On the other hand, Director of the NOVW, Cristina Frolov, declared that no open competition with Romania is aimed at the governmental level of the Republic of Moldova. “This request for collaboration is a consequence of the partnership principle. Romania imports 10-12% of the wine it consumes, and we want to take more from this import quota. Every year, the Romanian market grows by approximately 2.8%, as it happened in 2020, and we are interested in taking a maximum share of this percentage of imported wines without entering into direct competition with the Romanian producer,” the Moldovan official said. She also mentioned that Moldova aims at increasing the market share of wine production by at least 50% compared to 2020, and the number of producers present on the Romanian market – by at least 40%.

Source: ccir.ro

**

According to the data of the Romanian National Trade Register Office, the total value of Romania-Moldova trade was 1.7 billion euros at the end of last year and over 805 million euros at the end of May 2021. In July 2021, there were 6 522 companies from the Republic of Moldova in Romania, with a total capital value of 45.9 million euros.

The data of Moldova’s National Office of Vine and Wine showed that, in the first 7 months of 2021, the total quantity of bottled wine was about 27 million litres (registering an increase of 10% as compared to the same period last year), with a value of more than one billion lei, which is 32% more than the same period last year. Moldovan wines were awarded 956 medals at 32 international competitions in 2020.

Photo: ccir.ro