Featured

Interview with an experienced pilot: The fear of flying// VIDEO

Although planes are the safest means of transport, many of us are afraid of flying. Mihai Botnari, a pilot with 21 years of experience at Air Moldova, dismantles all the fears of flying. How worrying is the turbulence? What happens if a bird hits the engine? Or a lightning strike? What does an old plane represent?

Culture

The village of the first astronomer in the Republic of Moldova

Culture

Vîșcăuți, the Moldovan village where you feel like heaven

Reading Time: 9 minutesShe enters the house in a hurry and arranges the corner of the entrance mat. She leaves her purse and other items on the kitchen chair and starts washing the dishes. Then she goes to the second floor, changes the sheets on the beds, arranges the trinkets on the table, draws the curtains and opens the windows to aerate the room. From the window you can see the Nistru river, its banks covered with fresh vegetation. The woman sees to her tasks. She vacuums, she cleans the floors and starts all over again on the first floor.

Then she moves to the old house next door. Nobody was accommodated in this house yet, as everyone prefers “euro” repairs, as Lucia, the 52 years old administrator of the guest house, explains. But she doesn’t let the dust settle on the furniture and always has the rooms ready to accommodate guests.

The House of the Boyar is a guest house in the village of Vîșcăuți, Orhei, and can accommodate up to 8 persons. It is part of an eco-cultural touristic project “Bronze Half-moon” (“Semiluna de bronz”), which aims at attracting tourists in rural regions, offering them authentic experience, but it also promotes social entrepreneurship.

Besides involving the locals by creating jobs, the project also offers the opportunity and necessary support for the villagers to sell their products and services. Also, the profit is reinvested in the locality and its development. For example, now they work on developing a touristic trail through the forests of Vîșcăuți with all the necessary infrastructure, which will benefit the visitors of the village, as well as the locals.

Lucia quickly sweeps in the yard and takes out the trash. She managed to tidy up in just about two hours. A group of tourists just left and another one is coming. Lucia Frunză took off her apron and is ready to welcome the guests. “They come from Chișinău, they come from everywhere,” she says in a hurry.

Lucia remembers when she received a group of 18 people. At their request, she cooked them plăcinte, pot roast and mămăligă. But she decided to make them a surprise and prepared some mulled wine. “As a bonus. I have a special recipe. I add black pepper, sugar, lemon, oranges and a little vanilla. These give the wine such an arooomaaa.”

She is a very good cook. And one of her secrets is a special knife, which she carries with her from home to the guest house and back. It’s a cleaver with a wavy pattern blade, so when she cuts produce, it has jagged edges. When she makes soup, she cuts the potatoes, the carrots, the meat and the onion – she slices everything with it. Once she brought a bowl of soup to uncle Colea. “Oh, this soup with farfalle is so good, it’s like at a restaurant!,” recalls Lucia amused about the impression she made on the neighbor.

The meadow and the cave

Gheorghe and Ludmila Frunză live down the road from the guest house. When Lucia has too much on her plate, the old couple helps her out with cooking or with laundry. He is 74 years old, and she is 70. In summertime, the couple spends their second youth in Vîșcăuți. In winter, when it’s cold, they go back to Chișinău.

Gheorghe was born here, and he knows all the surroundings like his five fingers. He knows how to reach the Boyar’s Cave two ways: one is more difficult and the other one easier.

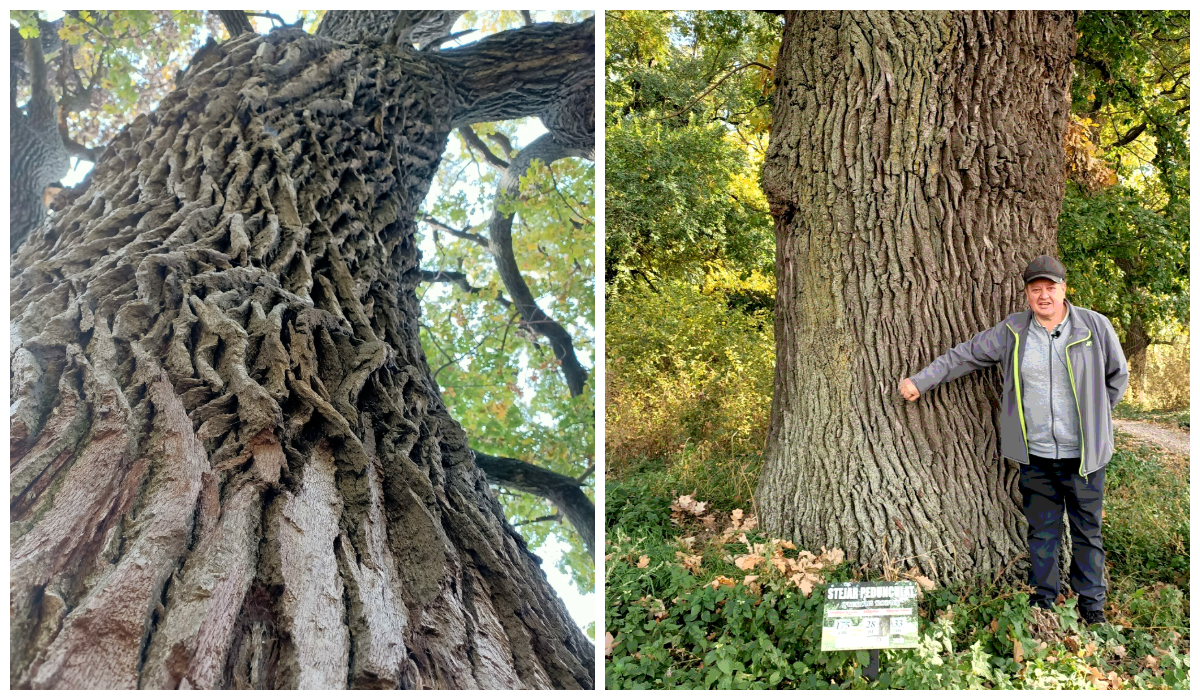

If you are in good shape and have the courage, you can reach the Boyar’s Cave through the ravine. But Gheorghe’s legs can’t keep up with this trail as he used to. The pathway to the cave goes between two rocky hills. You will step on the slippery rocks, washed by the cold water of the springs. You will climb the trees so thick, you can’t embrace with both hands, knocked down by the summer rain.

You will slowly advance towards the cave located up the hill, where you’ll see the Cornelian cherry dogwood full of hard-to-reach red berries, which local people pick for making compote. If you try and yell between the two rocky hills, your voice will not travel far. You will have no use of modern technologies, and your phone will only be good for taking pictures. Here you can breathe fresh cold air, while embraced by the silence dictated only by the murmur of the water.

Once you reach the cave, you need a lantern. On the walls you can see “V+M=LOVE”, but also hanging bats – almost embraced one next to another. There are three entrances to the cave and many labyrinths. No one knows exactly what are its measurements. There are some assumptions that it’s one kilometer long. But you can’t really reach its depths, because it collapsed a long time ago.

There are many legends about the origin of the cave. Gheorghe tells us that it used to be a quarry, tons of rock being extracted for the construction of churches.

Actually, according to archives, the cave was dug by the Sandino boyar around 1900 for storing wine barrels.

Locals say that during the two world wars, the cave was used as shelter for their grandparents and great-grandparents, and that they were guarded by the soldiers stationed in Vîșcăuți.

The old couple takes us on the river bank. “If you get on the boat and sail on the river, watching the forest… It’s such a beauty!,” Gheorghe tells us with excitement. He walks slowly and looks towards Nistru, watching the swans, the forest. “The air in Vîșcăuți almost makes you drunk,” he adds. He is followed by his wife Liuda and Daniel, a boy from the neighborhood.

They want to visit the three springs. It is said that the water of each of the springs has distinctive tastes. When they get to the place, they can see tourists’ traces: campfire ash, some pieces of paper. Tourists are not uncommon in these places. Gheorghe tells us that they come with their tents and spend a couple of days here fishing. He likes spending time with them. “All of them say that this is a nice quiet place”.

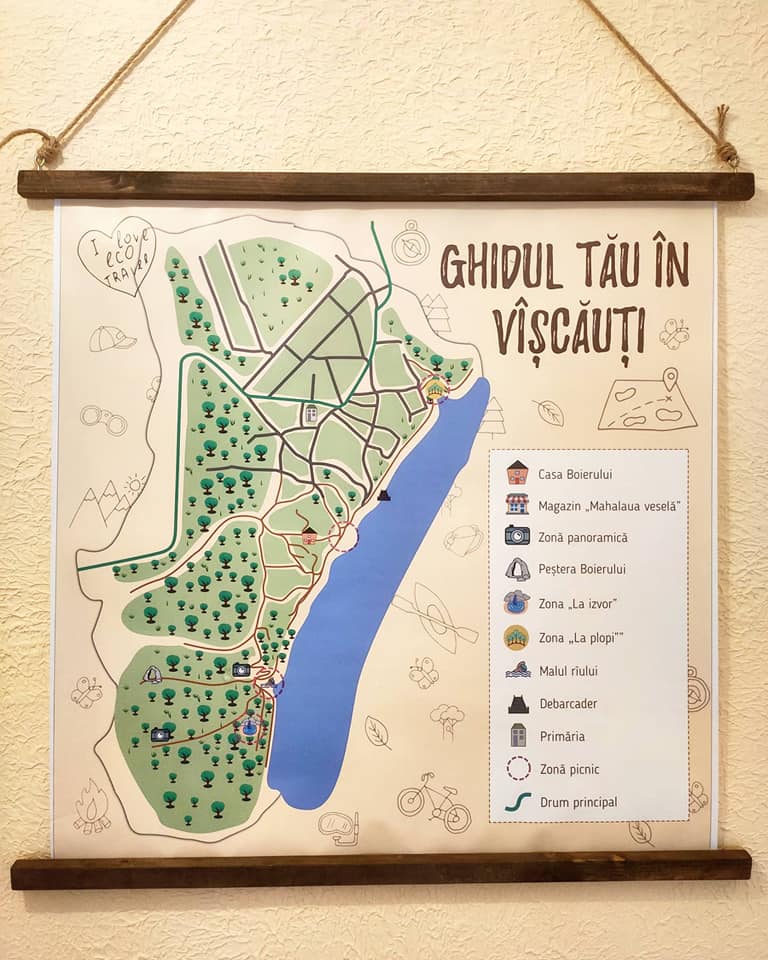

Map drawn for the tourists who visit the Boyar’s House

In Vîșcăuți you can rent a boat from the locals. You can also buy homemade bread, wine and free range chicken, fresh river fish, home grown vegetables. The village also has a beach, a picnic area, a wharf and a neighborhood called “The joyful neighborhood” due to the events organized here. From time to time, people gather here and cook fish soup or barbeque, they play some music, dance and party.

“The hill of Chirița” opens a view of Nistru river and the surrounding areas. “Now everything has dried-up… But when it’s green, the flowers there are wonderful!,” says Gheorghe.

“In Rață’s music video they showed the entire village. They filmed the forest and our meadow”, recalls Gheorghe. “There is also a song – My meadow. He sang it on TV many times,” adds Ludmila.

„Over the mountain, over the river – is my meadow,

Sometimes yearly, sometimes late – I take a walk there,

Over the mountain, over the river – flowers and roses,

Over the mountain, over the river – hidden memories.”

The lyrics to the song “My meadow”, sang by Moldovan singer Ion Rață, born in Vîșcăuți, where the music video was filmed.

Since the pandemic started, Ludmila and Gheorghe appreciate life in the village even more. “When the pandemic started, everyone was so agitated and scared. When we were in Chișinău, we would see all the ambulances and police cars throughout the entire city. But when we came here, it was like coming to heaven. When you get in the yard, you don’t need the mask any longer. We are peaceful here and we see to our chores. In Chișinău we didn’t have anything to do, except sitting on the benches outside. But here we exercise, we grow vegetables, fruits, we make canned food for winter,” Ludmila explains. She appreciates the tourists visiting the village, because the people have the opportunity to sell something to them. “They really don’t have a way to sell something in the village, no means to make a living.”

The luck and the happiness to be born at the river

Because the village is located on the banks of Nistru, the river is the one dictating the life in the region: it gives people water, it gives them food, but also leisure areas. Gheorghe remembers that especially during the soviet period he would visit his relatives on the other side of the river, in the village of Harmațca. They would barbeque under the willows near the river and then cross Nistru and continue their party under the willows of Vîșcăuți.

At the guest house, while stirring the pot roast, Lucia is humming a sad song. She is absorbed by the process and lets herself caught up in the moment:

Nistru, don’t drown me,

Nistru, don’t drown me,

Shai-rai-rai-ra, Shai-rai-rai-ra.

You don’t have the money to burry me,

You don’t have the money to burry me,

Shai-rai-rai-ra, Shai-rai-rai-ra.

“I woke up to this song. I woke up with my grandparents, with my parents, with the entire village singing it, and we learned it.” She grinds some cheese on a plate, and on another she puts some parmesan – so it’ll be tastier with the mămăliga. She puts some clay plates on the table and invites the guests.

“I am very proud to be born near the river,” says Lucia. She has happy memories of her childhood, when the winters were colder and the ice on the river could reach even 1 meter in depth. “Cars and tractors, even trucks with gas tanks would cross Nistru, driving towards the Transnistrian region,” she explains.

1 434 |

1 210 |

People live in VîșcăuțiSources: BNS, 2014 |

People live in HarmațcaSources: dubossary.ru, 2013 |

Even today, the bond between the two river banks is not lost. Lucia has relatives living in the village across the river, in Harmațca. “We have brothers and sisters, we have cousins, we are all related to each other. Because it’s a whole.”

Produced with the financial support of the European Union within the “Support to Confidence Building Measures” project, implemented by UNDP. The opinions expressed in this material do not necessarily reflect the official position of the EU or UNDP.

Featured

FC Sheriff Tiraspol victory: can national pride go hand in hand with political separatism?

Reading Time: 4 minutesA new football club has earned a leading place in the UEFA Champions League groups and starred in the headlines of worldwide football news yesterday. The Football Club Sheriff Tiraspol claimed a win with the score 2-1 against Real Madrid on the Santiago Bernabeu Stadium in Madrid. That made Sheriff Tiraspol the leader in Group D of the Champions League, including the football club in the groups of the most important European interclub competition for the first time ever.

International media outlets called it a miracle, a shock and a historic event, while strongly emphasizing the origin of the team and the existing political conflict between the two banks of the Dniester. “Football club from a pro-Russian separatist enclave in Moldova pulls off one of the greatest upsets in Champions League history,” claimed the news portals. “Sheriff crushed Real!” they said.

Moldovans made a big fuss out of it on social media, splitting into two groups: those who praised the team and the Republic of Moldova for making history and those who declared that the football club and their merits belong to Transnistria – a problematic breakaway region that claims to be a separate country.

Both groups are right and not right at the same time, as there is a bunch of ethical, political, social and practical matters that need to be considered.

Is it Moldova?

First of all, every Moldovan either from the right or left bank of Dniester (Transnistria) is free to identify himself with this achievement or not to do so, said Vitalie Spranceana, a sociologist, blogger, journalist and urban activist. According to him, boycotting the football club for being a separatist team is wrong.

At the same time, “it’s an illusion to think that territory matters when it comes to football clubs,” Spranceana claimed. “Big teams, the ones included in the Champions League, have long lost their connection both with the countries in which they operate, and with the cities in which they appeared and to which they linked their history. […] In the age of globalized commercial football, teams, including the so-called local ones, are nothing more than global traveling commercial circuses, incidentally linked to cities, but more closely linked to all sorts of dirty, semi-dirty and cleaner cash flows.”

What is more important in this case is the consistency, not so much of citizens, as of politicians from the government who have “no right to celebrate the success of separatism,” as they represent “the national interests, not the personal or collective pleasures of certain segments of the population,” believes the political expert Dionis Cenusa. The victory of FC Sheriff encourages Transnistrian separatism, which receives validation now, he also stated.

“I don’t know how it happens that the “proud Moldovans who chose democracy”, in their enthusiasm for Sheriff Tiraspol’s victory over Real Madrid, forget the need for total and unconditional withdrawal of Russian troops from Transnistria!” declared the journalist Vitalie Ciobanu.

Nowadays, FC Sheriff Tiraspol has no other choice than to represent Moldova internationally. For many years, the team used the Moldovan Football Federation in order to be able to participate in championships, including international ones. That is because the region remains unrecognised by the international community. However, the club’s victory is presented as that of Transnistria within the region, without any reference to the Republic of Moldova, its separatist character being applied in this case especially.

Is it a victory?

In fact, FC Sheriff Tiraspol joining the Champions League is a huge image breakthrough for the Transnistrian region, as the journalist Madalin Necsutu claimed. It is the success of the Tiraspol Club oligarchic patrons. From the practical point of view, FC Sheriff Tiraspol is a sports entity that serves its own interests and the interests of its owners, being dependent on the money invested by Tiraspol (but not only) oligarchs.

Here comes the real dilemma: the Transnistrian team, which is generously funded by money received from corruption schemes and money laundering, is waging an unequal fight with the rest of the Moldovan football clubs, the journalist also declared. The Tiraspol team is about to raise 15.6 million euro for reaching the Champions League groups and the amounts increase depending on their future performance. According to Necsutu, these money will go directly on the account of the club, not to the Moldovan Football Federation, creating an even bigger gab between FC Sheriff and other football clubs from Moldova who have much more modest financial possibilities.

“I do not see anything useful for Moldovan football, not a single Moldovan player is part of FC Sheriff Tiraspol. I do not see anything beneficial for the Moldovan Football Federation or any national team.”

Is it only about football?

FC Sheriff Tiraspol, with a total estimated value of 12.8 million euros, is controlled by Victor Gusan and Ilya Kazmala, being part of Sheriff Holding – a company that controls the trade of wholesale, retail food, fuels and medicine by having monopolies on these markets in Transnistria. The holding carries out car trading activities, but also operates in the field of construction and real estate. Gusan’s people also hold all of the main leadership offices in the breakaway region, from Parliament to the Prime Minister’s seat or the Presidency.

The football club is supported by a holding alleged of smuggling, corruption, money laundering and organised crime. Moldovan media outlets published investigations about the signals regarding the Sheriff’s holding involvement in the vote mobilization and remuneration of citizens on the left bank of the Dniester who participated in the snap parliamentary elections this summer and who were eager to vote for the pro-Russian socialist-communist bloc.

Considering the above, there is a great probability that the Republic of Moldova will still be represented by a football club that is not identified as being Moldovan, being funded from obscure money, growing in power and promoting the Transnistrian conflict in the future as well.

Photo: unknown