Opinion

Along lesser traveled roads: Moldova, a Legend in a Bottle

Darius Roby is a travel writer, translator, and an editor for Cluj.com, a city portal with information pertaining to life and tourism in Cluj-Napoca. He can be reached at [email protected]

This time he shard with us his impressions of the Cricova winery, one of the biggest in Moldova.

Winemaking is an unmistakable part of Moldova’s charm, noted throughout the centuries and today serving as a draw for modern-day tourists.

———–

Walking through the village of Dumbrava Roșie, Neamț County, Romania last year on a warm spring day, I noticed an interesting phenomenon. After a rather chaotic winter, it was the first definitely warm and sunny day of the year. To my amazement, as I continued down the road I noticed that at every house, there were people on ladders in unison pruning their grape wines for another year of cultivation and come autumn – wine production. It almost seemed to me that there was an unspoken “calling” that sent these Romanian Moldovans outside to begin caring for their vines at the beginning of spring. So passed the first day of the agricultural year, devoted to a tradition that is steeped in history and legend.

Wine has been produced along the northern shores of the Black Sea for a millennium. The neolithic transition from nomadic to sedentary forms of living may have led to wild strains of grapes found in modern-day Georgia being cultivated as early as 6000 BC. At the other end of the sea, in modern-day Moldova, archaeological discoveries at Varvarovca point to wine cultivation as early as 3000 BC. Grape production has remained central to agriculture in the Carpatho-Dniester-Pontic region over the ages and the wines of the region passed into the legends and folklore of the Moldovan people. I was once told a story in Soroca that once upon a time, the fortress was placed under siege by a host of Tatars and the siege lasted for months. The defenders, who were starved of food and water, found themselves rescued by storks who would drop bunches of grapes inside the central citadel, reinvigorating them, and ultimately inspiring them to withstand the Tatar siege.

Winemaking in the region has seen its ups and downs through the history, from King Burebista ordering the cutting of the Dacians’ vines, to government support under Russian imperial rule, to the devastating phylloxera outbreak towards the end of the 19th century. The outbreak led to the extinction or near-extinction of various native varieties of Moldovan grapes such as Pomană boierească or Firțigaia, which would be replaced by hardier French varieties with familiar names such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, and Chardonnay. Caucasian varieties such as Saperavi and Rkatsiteli have also been introduced. There are native varieties that can still be enjoyed today such as Fetească Albă, Plavai, or Rară Neagră, which in particular is blended with other varieties to make the legendary Negru de Purcari, but these account for only a small percentage (approximately 10%) of the grapes used for wine production today in the country.

There are four wine-making regions in Moldova: in the north there’s Bălți – famous for its dry wines, Valul lui Traian – the southern steppe region famous for its red wines, Stefan Voda – home of the Purcary winery, and Codru – where the famous Milestii Mici and Cricova wineries are found. I recently found myself at Cricova, seeing first hand that Moldova is underrated as a wine producer, and how important wine is to the soul of Moldovan people.

Approximately 10 miles away from Chisinau lies the Cricova winery. It is located in a town of the same name. I do not know the origin of the name. It seems to derive from the name “Cricău” and even deeper in the past it was once referred to as Vadul-Pietrei, perhaps due to the rocky area near the river Ichel, a tributary of the Dniester. To arrive at the winery you must follow Chișinăului Street, turning on the road heading towards the river right before passing the penitentiary. A descending road then takes you past some houses, a wonderful lookout point on the river, a gift-shop, two restaurants, and then the winery.

The cellars are carved into the limestone hills and cliffs that rise above the Ichel. Formerly a quarry for the extraction of stone, it is truly a city, situated 100 meters underground, with subterranean galleries that stretch for over 120 kilometers. It is also important to note that the cellars are very chilly, due to them being underground. I was reminded of the mines at Roșia Montană, feeling the sudden blast of cold air welcoming me as I again entered the underground world. The temperature is uniform, which aids in the production and preservation of the wines. The galleries are interestingly named, carrying the names of wine varieties – Chardonnay Street, Codru Street, Feteasca Street, etc. These initial galleries are filled with barrels dedicated to storing the particular wines on their respectively named streets. The name Codru is derived from the hilly forests of Central Moldova, a refuge in the past for people who lived in an unstable and dangerous part of the world. The Codru forests not only provided shelter for Moldovans, it also provided food, and Cricova’s Codru wine (a Cabernet-Sauvignon/Merlot blend) is made in its honor.

The cellars also plays host to a small museum that honors the history of wine-making in the country. There you will learn about fossils discovered at Naslavcea, attesting to the presence of wild grapes millions of years ago. There are also Greek amphorae, wine presses, as well as medieval documents that attest to wine cultivation in the region from the earliest of eras. The museum serves as a historical record of the importance of wine to the ancestors of Moldovans, it also shows evidence of foreign influences that further developed and advanced the craft.

Beyond can be found the National Collection of wines, preserving a myriad of historic and priceless wines dating back to the nineteenth century. Among these can be found the personal collection of Hermann Göring, a trophy of the Second World War. Many important personalities have visited the winery in the past ranging from Yuri Gagarin to Traian Basescu. The Soviet cosmonaut in particular remarked that he found it more difficult to leave the winery than it was returning from space after two days of drinking and partying at Cricova. Many of these famous visitors now have personal collections that are kept in the Cricova cellars. The wines are priceless, some unique in the sense that they were made from grape varieties that have since been lost to us. This treasure is not only part of Moldova’s national heritage, but also part of what makes us unique and interesting as humans. Each bottle of wine tells a special story, and how would I have loved to know the story of each bottle kept in the National Collection.

Moving on, one reaches the famous tasting halls. The European Room is where most wine tastings take place, a spacious room with a long table and many chairs on each side. There are stained glass windows that depict grape vines during the seasons of the year. It is a perfect space for meetings, reunions, conferences, etc. It is here where our group was hosted for a wine tasting where we sampled reds, whites, as well as excellent champagne while learning the fine details of the art of wine tasting.

What a memorable experience it was! While little more than half of the group seems to have had enough knowledge of Romanian to understand the guide, wine has a way of bringing people together in a way that ultimately leads to greater understanding, despite linguistic differences. While sitting at the table, I looked to my right and tried to explain to the man sitting next to me that he was holding his glass incorrectly. He smiled and said “Italiano!” My mind raced back in time to when I visited Italy for the first time and the words “Piacere di conoscerti, sono Americano” magically sprang from my tongue. He laughed and toasted me, while explaining to his pal in excitement something in Italian that probably went to the tune of “We have an American among us and he knows Italian!” (Note: I don’t know Italian…beyond a couple of words) Visibly drunk, a group of Turks asked them, “Where is that guy from?” in English and someone responded “America!” and they subsequently raised their glasses to say “Cheers!” Laughing to myself that this situation is getting out of control, a man raised his glass to me and said “I am from Serbia!” and… maybe it was the effects of 5 glasses of wine but I shouted “Slava Srbija!” to his astonishment. It was a merry experience, one brought to you by the kind folks at Cricova and a group of foreigners with no tolerance for alcohol.

Believe it or not, the European Room is the least impressive of Cricova’s tasting halls. There is the “Seabed” tasting room, designed for only 10 people, that looks like something ripped from a Jules Verne novel. The green and blue aquatic decor gives the impression that you are on the Nautilus and is exploring the world over a glass of wine. There’s the “Casa Mare” that is reminiscent of a traditional Moldovan home, the “Fireplace room” with a rustic hunting style that looks perfect for diplomatic conferences, and finally, the smallest room – “Presidential” room, where I imagined to myself that this is probably where Vladimir Putin celebrated his 50th birthday.

Departing the cellars, the sunny sky and the cold early spring wind slapping your face is a wonderful wake up call from the adventures of the tasting room. In a stroke of marketing brilliance, there is a gift store next to the exit, designed for drunk wine connoisseurs to splurge. There I found my new Turkish, Italian, and Serbian friends filling their cars and boxes with wine, while I picked out a nice bottle for myself, Cricova Codru feeling most appropriate. So ended another adventure, one that was educational and thought provoking. Moldovan wines are one of Eastern Europe’s best kept secrets, extremely popular in the former Soviet Union, second only maybe to those from Georgia. I wonder what it would take to raise their profile in the West, to put them on the same level of those from France, Italy, or Australia. This charming little country between the Prut and Dniester rivers may not be the largest wine producer in the world, but each bottle tells a story of history, legends, and survival that is unique in the world.

Opinion

Russia And Ukraine At The Beginning of 2022

This opinion piece was written by Dr. Nicholas Dima. Dr. Dima was formerly a Professor of Geography and Geopolitics at Djibouti University, St. Mary’s University College and James Madison University. From 1975 to 1985 and from 1989 to 2001, Dr. Dima was a Writer and Field Reporter at Voice of America. The opinion does not necessarily represent the opinion of the editorial staff of Moldova.org.

***

The 21st Century Russian Federation is a rebirth of the 19-th Century Tsarist Empire; a huge territory inhabited by hundreds of ethnic groups held together by an authoritarian government. Having acquired a diversity of lands and peoples that would not freely want to be together, Moscow has to be on guard. It has to keep an eye on those who are inside the federation and to make sure that no outsiders threaten its territory. Otherwise, in a nutshell, Ukraine is Russia’s biggest dilemma and Russia is Ukraine’s biggest nightmare!

In 1991 Moscow agreed reluctantly to the dissolution of the former USSR. Ukraine became independent and consented to give up its nuclear arsenal inherited from the Soviet Union in exchange for territorial guaranties. Russia did not keep its engagement. It violated the Minsk protocol and in 2014, after a hybrid war, annexed Crimea. At the same time, pro-Russian forces took over two important eastern Ukrainian regions, Lugansk and Donetsk, where the population is ethnically mixed and somehow pro-Russian.

Since the annexation of Crimea, Moscow has strengthened its military presence in the peninsula and in the Black and Azov Seas. Furthermore, it built a strategic bridge that connects Crimea with the Russian mainland. Then, Russia began to reject NATO activities in East Europe and to denounce the presence of the US Navy in the Black Sea as provocations. In order to counter NATO, Russia also brought some of its warships from the Caspian Sea to the Black Sea through the Volga-Don Canal.

During recent years, Ukraine approached the United States and NATO and asked for assistance and, eventually, for membership in the EU and possibly NATO. For Moscow, however, Ukraine is an essential buffer zone against the West. With President Vladimir Putin lamenting the dismemberment of the USSR and embracing the traditional Russian expansionist mentality, the perspective of Ukraine’s NATO membership would be an existential threat.

The current situation at the Russo-Ukrainian border is tense and the stakes are high. Neither country is satisfied with the status quo, but the choices are very risky. The important Donbas region of East Ukraine, controlled by pro-Russian forces, is in a limbo. Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky is losing support among the people and must defend his country’s integrity. Currently, Putin has the upper hand and military superiority on his side, but using brute force in the conflict could trigger further Western economic sanctions and even military hostility.

For now it seems that Moscow is mainly posturing, but the true Russian intentions are not clear. Thus, a miscalculation could trigger a catastrophe of international proportions. No one knows how the events will play out, but the danger is obvious. Moscow is playing with fire. Apparently, it does not want a full war, neither the current stalemate, nor a retreat. What does it want? It seems that Moscow knows what it wants, but not necessarily what it can!

Regionally, the situation between Europe and Russia is complex and internationally the world is confronted with threatening new realignments. With the help of Russia, Belarus has encouraged thousand of Middle East migrants to assail the Polish border and the European Union. Poland has mobilized its forces and NATO and EU are on alert. The three Baltic countries also feel threatened. And the recent Russo-Chinese economic cooperation and military rapprochement reinforce the international apprehension.

Since the dissolution of the USSR, Russia went through several uneasy stages. During the first years of transition toward a new political system Russia experienced economic decline and popular unrest. Then, Putin took over and managed to stabilize the country. Russia opted for security and stability instead of political democracy and economic prosperity. At the same time, Kremlin focused its resource on the military and strengthened Russia’s war capacity.

For the time being, Russia may want to perpetuate the current situation and to keep Ukraine under its thumb. However, things are not static and sometimes they move unpredictably. What if Ukraine does become a NATO member? Then, it will be impossible for Russia to challenge Kyiv without triggering a devastating war. On the other hand, waiting is not in Russia’s advantage. Demographically, ethnic Russians are declining and the non-Russians, mostly Muslims, are fast increasing. The continuous emigration to the West of many Russians is not helping the population balance either. This trend will almost certainly renew old conflicts especially in the unsettled Caucasus region…

Attacking Ukraine now, overtly or through a hybrid war, would be risky for Russia and would not bring a lasting solution to the dispute. The war could destabilize Kyiv and even dismember Ukraine, but it would also destabilize the Russian Federation. The present tension will probably be diffused, but the next time around, in about 10 to 20 years, Putin will be gone, Moscow itself will be in disarray, Caucasian Muslims will be asking openly for independence and Ukraine will be ready and capable to fight Russia.

A Russo-Ukrainian war, now or later, will immediately have regional effects engaging Belarus and most likely Poland, the Baltic States, Moldova, Romania and implicitly NATO. Romania, for example, will follow its western allies, but it could not ignore the fact that certain formerly Romanian lands are now part of Ukraine. As for Moldova, beyond the facts that Moldovans are Romanians, its Transnistrian (Transdnestr) area is entirely under Russian control and in an eventual war will be used by Moscow against Ukraine.

Nicholas Dima, January 1, 2022

Culture

The village of the first astronomer in the Republic of Moldova

Culture

Vîșcăuți, the Moldovan village where you feel like heaven

Reading Time: 9 minutesShe enters the house in a hurry and arranges the corner of the entrance mat. She leaves her purse and other items on the kitchen chair and starts washing the dishes. Then she goes to the second floor, changes the sheets on the beds, arranges the trinkets on the table, draws the curtains and opens the windows to aerate the room. From the window you can see the Nistru river, its banks covered with fresh vegetation. The woman sees to her tasks. She vacuums, she cleans the floors and starts all over again on the first floor.

Then she moves to the old house next door. Nobody was accommodated in this house yet, as everyone prefers “euro” repairs, as Lucia, the 52 years old administrator of the guest house, explains. But she doesn’t let the dust settle on the furniture and always has the rooms ready to accommodate guests.

The House of the Boyar is a guest house in the village of Vîșcăuți, Orhei, and can accommodate up to 8 persons. It is part of an eco-cultural touristic project “Bronze Half-moon” (“Semiluna de bronz”), which aims at attracting tourists in rural regions, offering them authentic experience, but it also promotes social entrepreneurship.

Besides involving the locals by creating jobs, the project also offers the opportunity and necessary support for the villagers to sell their products and services. Also, the profit is reinvested in the locality and its development. For example, now they work on developing a touristic trail through the forests of Vîșcăuți with all the necessary infrastructure, which will benefit the visitors of the village, as well as the locals.

Lucia quickly sweeps in the yard and takes out the trash. She managed to tidy up in just about two hours. A group of tourists just left and another one is coming. Lucia Frunză took off her apron and is ready to welcome the guests. “They come from Chișinău, they come from everywhere,” she says in a hurry.

Lucia remembers when she received a group of 18 people. At their request, she cooked them plăcinte, pot roast and mămăligă. But she decided to make them a surprise and prepared some mulled wine. “As a bonus. I have a special recipe. I add black pepper, sugar, lemon, oranges and a little vanilla. These give the wine such an arooomaaa.”

She is a very good cook. And one of her secrets is a special knife, which she carries with her from home to the guest house and back. It’s a cleaver with a wavy pattern blade, so when she cuts produce, it has jagged edges. When she makes soup, she cuts the potatoes, the carrots, the meat and the onion – she slices everything with it. Once she brought a bowl of soup to uncle Colea. “Oh, this soup with farfalle is so good, it’s like at a restaurant!,” recalls Lucia amused about the impression she made on the neighbor.

The meadow and the cave

Gheorghe and Ludmila Frunză live down the road from the guest house. When Lucia has too much on her plate, the old couple helps her out with cooking or with laundry. He is 74 years old, and she is 70. In summertime, the couple spends their second youth in Vîșcăuți. In winter, when it’s cold, they go back to Chișinău.

Gheorghe was born here, and he knows all the surroundings like his five fingers. He knows how to reach the Boyar’s Cave two ways: one is more difficult and the other one easier.

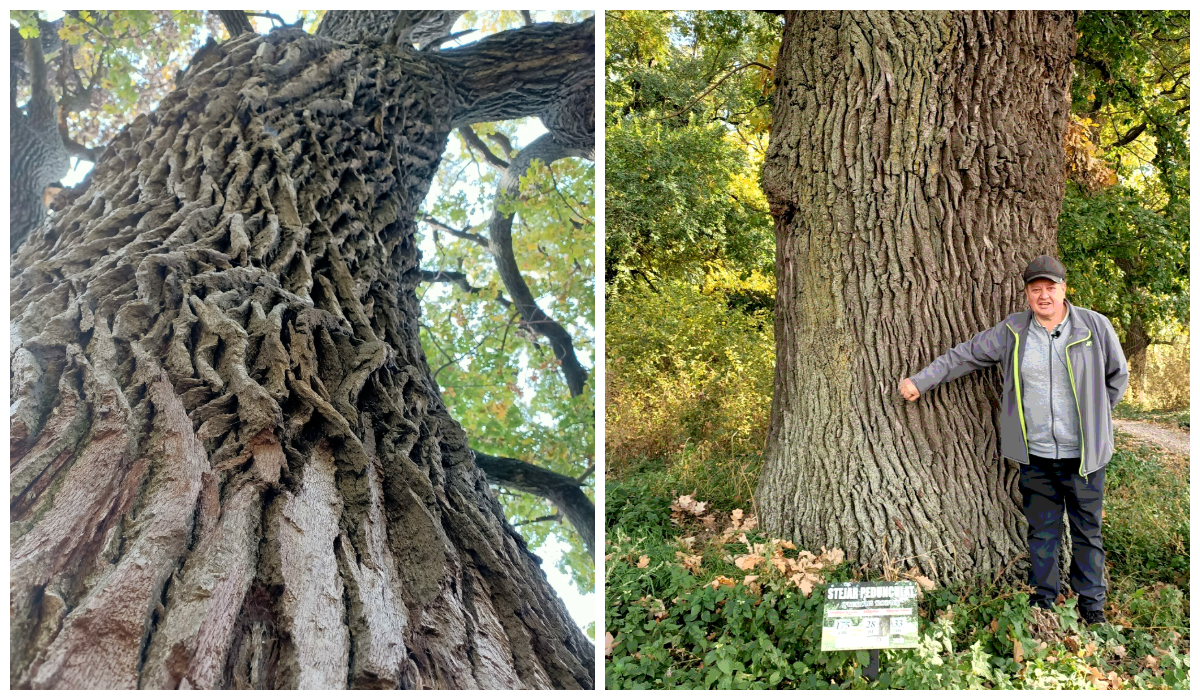

If you are in good shape and have the courage, you can reach the Boyar’s Cave through the ravine. But Gheorghe’s legs can’t keep up with this trail as he used to. The pathway to the cave goes between two rocky hills. You will step on the slippery rocks, washed by the cold water of the springs. You will climb the trees so thick, you can’t embrace with both hands, knocked down by the summer rain.

You will slowly advance towards the cave located up the hill, where you’ll see the Cornelian cherry dogwood full of hard-to-reach red berries, which local people pick for making compote. If you try and yell between the two rocky hills, your voice will not travel far. You will have no use of modern technologies, and your phone will only be good for taking pictures. Here you can breathe fresh cold air, while embraced by the silence dictated only by the murmur of the water.

Once you reach the cave, you need a lantern. On the walls you can see “V+M=LOVE”, but also hanging bats – almost embraced one next to another. There are three entrances to the cave and many labyrinths. No one knows exactly what are its measurements. There are some assumptions that it’s one kilometer long. But you can’t really reach its depths, because it collapsed a long time ago.

There are many legends about the origin of the cave. Gheorghe tells us that it used to be a quarry, tons of rock being extracted for the construction of churches.

Actually, according to archives, the cave was dug by the Sandino boyar around 1900 for storing wine barrels.

Locals say that during the two world wars, the cave was used as shelter for their grandparents and great-grandparents, and that they were guarded by the soldiers stationed in Vîșcăuți.

The old couple takes us on the river bank. “If you get on the boat and sail on the river, watching the forest… It’s such a beauty!,” Gheorghe tells us with excitement. He walks slowly and looks towards Nistru, watching the swans, the forest. “The air in Vîșcăuți almost makes you drunk,” he adds. He is followed by his wife Liuda and Daniel, a boy from the neighborhood.

They want to visit the three springs. It is said that the water of each of the springs has distinctive tastes. When they get to the place, they can see tourists’ traces: campfire ash, some pieces of paper. Tourists are not uncommon in these places. Gheorghe tells us that they come with their tents and spend a couple of days here fishing. He likes spending time with them. “All of them say that this is a nice quiet place”.

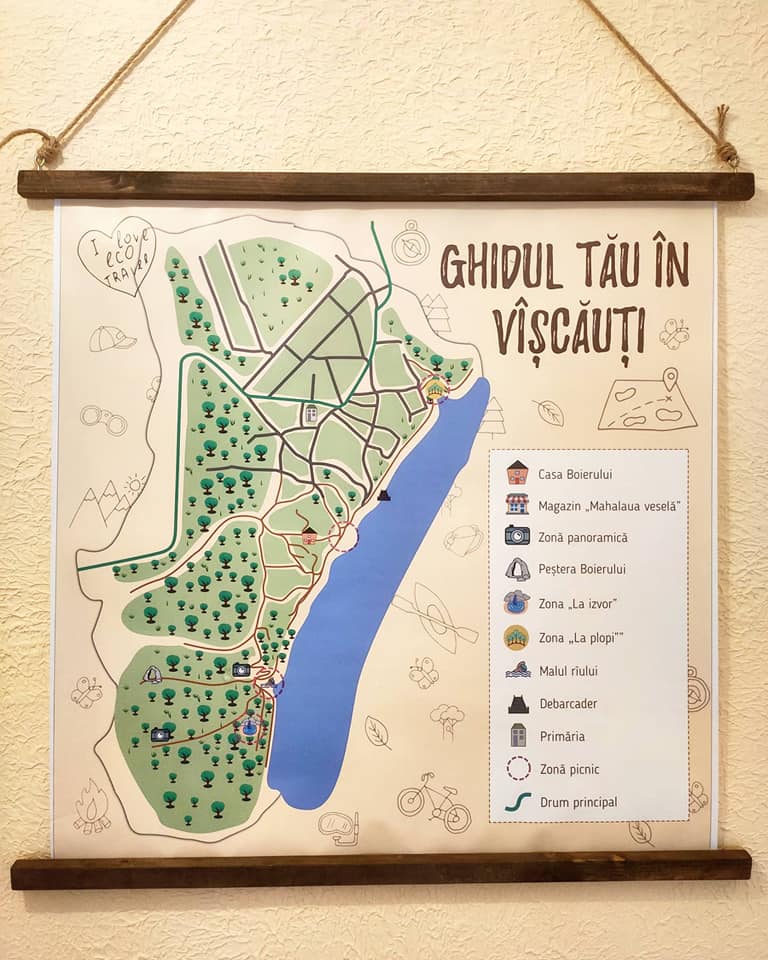

Map drawn for the tourists who visit the Boyar’s House

In Vîșcăuți you can rent a boat from the locals. You can also buy homemade bread, wine and free range chicken, fresh river fish, home grown vegetables. The village also has a beach, a picnic area, a wharf and a neighborhood called “The joyful neighborhood” due to the events organized here. From time to time, people gather here and cook fish soup or barbeque, they play some music, dance and party.

“The hill of Chirița” opens a view of Nistru river and the surrounding areas. “Now everything has dried-up… But when it’s green, the flowers there are wonderful!,” says Gheorghe.

“In Rață’s music video they showed the entire village. They filmed the forest and our meadow”, recalls Gheorghe. “There is also a song – My meadow. He sang it on TV many times,” adds Ludmila.

„Over the mountain, over the river – is my meadow,

Sometimes yearly, sometimes late – I take a walk there,

Over the mountain, over the river – flowers and roses,

Over the mountain, over the river – hidden memories.”

The lyrics to the song “My meadow”, sang by Moldovan singer Ion Rață, born in Vîșcăuți, where the music video was filmed.

Since the pandemic started, Ludmila and Gheorghe appreciate life in the village even more. “When the pandemic started, everyone was so agitated and scared. When we were in Chișinău, we would see all the ambulances and police cars throughout the entire city. But when we came here, it was like coming to heaven. When you get in the yard, you don’t need the mask any longer. We are peaceful here and we see to our chores. In Chișinău we didn’t have anything to do, except sitting on the benches outside. But here we exercise, we grow vegetables, fruits, we make canned food for winter,” Ludmila explains. She appreciates the tourists visiting the village, because the people have the opportunity to sell something to them. “They really don’t have a way to sell something in the village, no means to make a living.”

The luck and the happiness to be born at the river

Because the village is located on the banks of Nistru, the river is the one dictating the life in the region: it gives people water, it gives them food, but also leisure areas. Gheorghe remembers that especially during the soviet period he would visit his relatives on the other side of the river, in the village of Harmațca. They would barbeque under the willows near the river and then cross Nistru and continue their party under the willows of Vîșcăuți.

At the guest house, while stirring the pot roast, Lucia is humming a sad song. She is absorbed by the process and lets herself caught up in the moment:

Nistru, don’t drown me,

Nistru, don’t drown me,

Shai-rai-rai-ra, Shai-rai-rai-ra.

You don’t have the money to burry me,

You don’t have the money to burry me,

Shai-rai-rai-ra, Shai-rai-rai-ra.

“I woke up to this song. I woke up with my grandparents, with my parents, with the entire village singing it, and we learned it.” She grinds some cheese on a plate, and on another she puts some parmesan – so it’ll be tastier with the mămăliga. She puts some clay plates on the table and invites the guests.

“I am very proud to be born near the river,” says Lucia. She has happy memories of her childhood, when the winters were colder and the ice on the river could reach even 1 meter in depth. “Cars and tractors, even trucks with gas tanks would cross Nistru, driving towards the Transnistrian region,” she explains.

1 434 |

1 210 |

People live in VîșcăuțiSources: BNS, 2014 |

People live in HarmațcaSources: dubossary.ru, 2013 |

Even today, the bond between the two river banks is not lost. Lucia has relatives living in the village across the river, in Harmațca. “We have brothers and sisters, we have cousins, we are all related to each other. Because it’s a whole.”

Produced with the financial support of the European Union within the “Support to Confidence Building Measures” project, implemented by UNDP. The opinions expressed in this material do not necessarily reflect the official position of the EU or UNDP.