Tourism

Darius Roby: Orheiul Vechi- A Window on the Past

October is a month of great change. The grapes have been cut and already pressed into next year’s wine, the days become noticeably darker and shorter, and the weather begins to take a turn for the worst as we say good bye to the last vestiges of summer. One such morning found me in Moldova, breathing the chilly air of harvest with its rumors of winter in search of one of the country’s historical and archaeological treasures.

I would recommend reading my previous account regarding a visit to Soroca in order to get a feel of arriving in the small Eastern European country, sandwiched between Romania and Ukraine. In regards to this tale, the Sun does not rise until almost 8 in the morning in early October, therefore my experience of arriving in Chișinău revolved around the shadow of forests obscured by the darkness of the night. Hopping off the bus under the night sky, I saw a few signs that the day would soon arrive – trolleybuses filled with people on their way to work, a lady strolling in the park near the cathedral, workers sweeping the streets clean of autumn leaves. Passing the parliament building, I saw a camp of tents and flags guarded by police. It was a scene not unlike what I had seen on Khreshchatyk Street in Kiev last summer. Pretty much, life seemed normal in the capital of Moldova on a Saturday morning.

Wandering down Ștefan cel Mare și Sfînt Street led me to the Central Market on Tighina Street. As I turned towards the east, I noticed the first light of the morning Sun peeking from the direction of the Ciocana neighborhood. I do not wish to go off on a tangent and get into deep detail about how interesting the market itself is, as it would deserve an article to itself. Needless to say, it is the commercial heart of the city, where one can literally find anything ranging from fruits, vegetables, and meats to clothes, boots, and fur hats. One could spend hours exploring the stalls there, sampling a bit of everything, and leaving with your pockets noticeably lighter than they were upon arrival.

Markets can be chaotic places, especially when they also have a full blown bus station. I had found the Autogara Centrala, and a quick look around revealed to me locations that I was not quite familiar with – mostly small villages around the country. A bit of exploring and asking around found what I was looking for – a mini-bus heading in the direction of Orhei. My target was no Orhei in particular but rather the villages of Trebujeni and Butuceni. “Going to Orheiul Vechi?”, I sleepily asked the driver in Romanian. After his affirmation, I climbed into the bus, wearily threw off my backpack and noticed an old man staring at me. Not shy about getting into conversations while traveling, we began talking and discussed everything from how to make wine to the obvious question regarding why is an American guy traveling alone in Moldova. I found myself laughing at his account of how he once made himself “black” due to standing in a basin and crushing Rară Neagră grapes until his entire body was covered with the dark red juice of the berries.

I imagine that by now the reader is wondering the same thing – what was I doing in Moldova on a chilly autumn day? My objective was to visit the ethno-cultural and archaeological complex at Orheiul Vechi, located along the River Răut in Central Moldova. It is one of those treasures that everyone in Moldova knows about and probably has visited, but almost no one outside of the country has ever heard of. I had made a mental note to visit the place years ago after hearing about it from aquaintances who lived not too far away in Ciocîlteni. It had sat on my list of interesting (and rather obscure) places to visit in Eastern Europe for years now and I was glad to had finally found the time to explore. Continuing my conversation with the man on the bus, he assured me that the site was very beautiful and that I would enjoy it.

A few minutes later, the bus left Chișinău and headed north on the main highway that connects the capital to most cities in northern Moldova. The trip was not a long one due to the excellent condition of the road, and it

was very picturesque. We passed through little villages and by farms that were colored with vibrant browns, reds, yellows, and oranges. The architecture that I saw was not dissimilar to what one could find in Eastern Romania save for the onion domed churches. Since the harvest had already been largely taken care of, I did not see many people outside working. We were however greeted with a mooo! by a lonely cow feasting on dying grass as the bus sped by. Autumn is the time of year to enjoy and celebrate the fruits of the Earth’s bosom, especially with the harsh winter being not too far away. I have always felt attracted by this beautiful little country, almost forgotten and ignored due to its difficult geopolitical situation. If Ukraine was once the breadbasket of the Soviet Union, then Moldova was its orchard due to the grapes, plums, apricots, and apples that can be found all over the country.

After some time, the bus arrived in Trebujeni and my eyes widened to see the canyon that encompasses and meanders around the River Răut. We live in the age of Wikipedia and Google so I already knew what the place would look like, but it does not prepare one for seeing such a dramatic shift in elevation in a mostly steppe country. At the summit of one precipice I saw a little church built in the Russian style as well as what appeared to be a cave monastery, beyond it was an even larger precipice, with the same vibrant brows, reds, yellows, and oranges painting it in autumn beauty. After crossing the river and arriving at Butuceni, I left the bus where another passenger kindly told me that the same bus would return at noon and I could take it to return to Chișinău. She also pointed me to an Info Point station where I could buy tickets and visit their museum. I am very appreciative of such hospitality, especially because I was at the time wondering the same exact thing. Walking back across the river led me to the Info Point where there were some women having tea and talking among themselves. I inquired about ticket prices, bought a guide book, and after a small conversation (the usual: How did you learn Romanian? Where are you from? Do you like Moldova?) I thanked them for their help and spent some time examining the interesting artifacts in the museum.

Orheiul Vechi was settled thousands of years ago by inhabitants of the Cucuteni culture and there were artifacts to testify to this. The museum also housed artifacts from the Geto-Dacian period. The town seemed to have enjoyed its greatest prosperity during the rule of the Mongols of the Golden Horde through its status as a Moldovan fortress until the sixteenth century. Under the Mongols the settlement was known as Yangi-Shehr and along the road towards Trebujeni one can find the remains of a Tatar bath house that once serviced the inhabitants. There is also evidence of Islamic worship due to the nearby ruins of a mosque with a minaret along with Arabic inscriptions. The Mongols abandoned the Carpathian-Dniestrian region around 1369 and the area was consolidated under the Moldovan Principality. Orhei served, along with Hotin, Soroca, Tighina, and Cetatea Alba, as an important fortress guarding the eastern borders of the principality along the River Dniester. Along the road, one can find the ruins of the residence of the governor (pîrcălab), attesting to the medieval importance of Orhei.

Climbing the hill towards the church one can find evidence of Geto-Dacian earthen and stone fortifications. It appears that once upon a time, there was once a great oval fortification that served as a fortress for the Geto-Dacians in the region. Artifacts consisting of Greek black vase pottery had been discovered here so I assume that there were trade links between the locals and the Greeks of the Black Sea colonies. Furthermore, there is a side path that leads to a cave opening to a tunnel that leads to a small monastery complex inside of the hill. The cave monastery is known as Peștera and there can be found residences for the monks as well as a small chapel with a beautiful iconostasis. There is also a nave, narthex, as well as a porch balcony that offers a commanding view of the Răut valley. From what I was told, the Peștera Hermitage dates from the early nineteenth century and serves as the parish of the village. Above the complex, at the summit of the canyon, along the cliff edge is

found a massive stone cross dating from the eighteenth century. I was told by a couple that was traveling there that the cross confers health and grants wishes to those who hug and walk around it.

Beyond it lies a church dedicated to the Assumption of the Virgin Mary. It is surrounded by a stone wall where within one can enjoy the garden and lose oneself in this quiet corner of paradise while listening to the hymns of the Orthodox liturgy.

The open air museum at Orheiul Vechi is massive and one would require an entire day to discover everything there is to see there. A quick look around at the other cliff walls will reveal openings to numerous cave monasteries – both accessible and inaccessible. They date from the 15th-18th centuries and some, for example the Pîrcălab Bosie Monastery, have carved inscriptions in both Slavonic and Romanian, both written in the Cyrillic script. These inscriptions reveal the names of people who lived there during the monastery’s heyday – Bosie, the Moldovan pîrcălab, along with Vasile Andeescul, Razmeritse Leka, as well as Stetsi Hatman, the leader of a group of Ukrainians that wintered in nearby Ivancea in 1689. Ultimately, Orheiul Vechi would be destroyed due to the repeated invasions launched by the Crimean Tatars into the Moldovan territory. The seat of local power would be transferred west to modern day Orhei, which continues to be a city of national importance to this present day.

The village of Butuceni proper serves as a wonderful place for lovers of ethnography and traditional Moldovan life. To the south of the Assumption church lies a cemetery, and beyond that lies the homes of the people who call this beautiful village home. It is not a large settlement, and the main road leading from Trebujeni is in fact, the only road. There are many examples of Moldovan traditional architecture and the people are very friendly and hospitable. During my walk there, for one reason or another, I found myself with a cup of homemade wine in my hand, and shortly afterwards – cognac. There are accommodation options there for those who wish to spend more than a day in this most interesting open air museum where one can enjoy a warm bed, a quiet atmosphere, and the wonders of Moldovan cuisine.

Orheiul Vechi is an open air museum of ethnography and history that I would recommend to anyone who visits Moldova. Regardless of whether one wishes to stay for a couple of hours or a couple of days, there are enough interesting things to see there that will satisfy one’s thirst for adventure. The location is even more accentuated by the chilly air and the vibrant spirit of the autumn harvest as it is a time of plenty – and therefore warmer hearts. There is an air of victory that comes with the autumn, the survival of another year while facing down the coming challenge of winter. I am glad that I decided to make this trip during the autumn, as this period comes with its own special beauty that cannot be found during the summer. It is like comparing the bright smile of a blooming sunflower with the solemn and perilous beauty of a rusalka.

Culture

The village of the first astronomer in the Republic of Moldova

Culture

Vîșcăuți, the Moldovan village where you feel like heaven

Reading Time: 9 minutesShe enters the house in a hurry and arranges the corner of the entrance mat. She leaves her purse and other items on the kitchen chair and starts washing the dishes. Then she goes to the second floor, changes the sheets on the beds, arranges the trinkets on the table, draws the curtains and opens the windows to aerate the room. From the window you can see the Nistru river, its banks covered with fresh vegetation. The woman sees to her tasks. She vacuums, she cleans the floors and starts all over again on the first floor.

Then she moves to the old house next door. Nobody was accommodated in this house yet, as everyone prefers “euro” repairs, as Lucia, the 52 years old administrator of the guest house, explains. But she doesn’t let the dust settle on the furniture and always has the rooms ready to accommodate guests.

The House of the Boyar is a guest house in the village of Vîșcăuți, Orhei, and can accommodate up to 8 persons. It is part of an eco-cultural touristic project “Bronze Half-moon” (“Semiluna de bronz”), which aims at attracting tourists in rural regions, offering them authentic experience, but it also promotes social entrepreneurship.

Besides involving the locals by creating jobs, the project also offers the opportunity and necessary support for the villagers to sell their products and services. Also, the profit is reinvested in the locality and its development. For example, now they work on developing a touristic trail through the forests of Vîșcăuți with all the necessary infrastructure, which will benefit the visitors of the village, as well as the locals.

Lucia quickly sweeps in the yard and takes out the trash. She managed to tidy up in just about two hours. A group of tourists just left and another one is coming. Lucia Frunză took off her apron and is ready to welcome the guests. “They come from Chișinău, they come from everywhere,” she says in a hurry.

Lucia remembers when she received a group of 18 people. At their request, she cooked them plăcinte, pot roast and mămăligă. But she decided to make them a surprise and prepared some mulled wine. “As a bonus. I have a special recipe. I add black pepper, sugar, lemon, oranges and a little vanilla. These give the wine such an arooomaaa.”

She is a very good cook. And one of her secrets is a special knife, which she carries with her from home to the guest house and back. It’s a cleaver with a wavy pattern blade, so when she cuts produce, it has jagged edges. When she makes soup, she cuts the potatoes, the carrots, the meat and the onion – she slices everything with it. Once she brought a bowl of soup to uncle Colea. “Oh, this soup with farfalle is so good, it’s like at a restaurant!,” recalls Lucia amused about the impression she made on the neighbor.

The meadow and the cave

Gheorghe and Ludmila Frunză live down the road from the guest house. When Lucia has too much on her plate, the old couple helps her out with cooking or with laundry. He is 74 years old, and she is 70. In summertime, the couple spends their second youth in Vîșcăuți. In winter, when it’s cold, they go back to Chișinău.

Gheorghe was born here, and he knows all the surroundings like his five fingers. He knows how to reach the Boyar’s Cave two ways: one is more difficult and the other one easier.

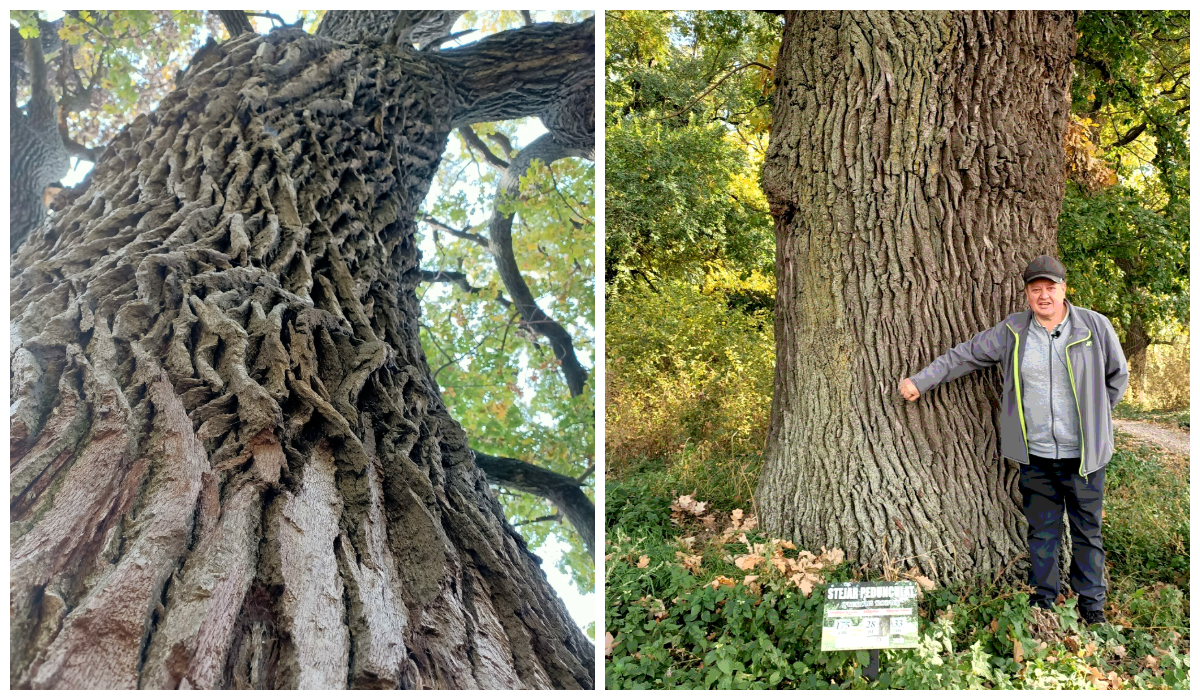

If you are in good shape and have the courage, you can reach the Boyar’s Cave through the ravine. But Gheorghe’s legs can’t keep up with this trail as he used to. The pathway to the cave goes between two rocky hills. You will step on the slippery rocks, washed by the cold water of the springs. You will climb the trees so thick, you can’t embrace with both hands, knocked down by the summer rain.

You will slowly advance towards the cave located up the hill, where you’ll see the Cornelian cherry dogwood full of hard-to-reach red berries, which local people pick for making compote. If you try and yell between the two rocky hills, your voice will not travel far. You will have no use of modern technologies, and your phone will only be good for taking pictures. Here you can breathe fresh cold air, while embraced by the silence dictated only by the murmur of the water.

Once you reach the cave, you need a lantern. On the walls you can see “V+M=LOVE”, but also hanging bats – almost embraced one next to another. There are three entrances to the cave and many labyrinths. No one knows exactly what are its measurements. There are some assumptions that it’s one kilometer long. But you can’t really reach its depths, because it collapsed a long time ago.

There are many legends about the origin of the cave. Gheorghe tells us that it used to be a quarry, tons of rock being extracted for the construction of churches.

Actually, according to archives, the cave was dug by the Sandino boyar around 1900 for storing wine barrels.

Locals say that during the two world wars, the cave was used as shelter for their grandparents and great-grandparents, and that they were guarded by the soldiers stationed in Vîșcăuți.

The old couple takes us on the river bank. “If you get on the boat and sail on the river, watching the forest… It’s such a beauty!,” Gheorghe tells us with excitement. He walks slowly and looks towards Nistru, watching the swans, the forest. “The air in Vîșcăuți almost makes you drunk,” he adds. He is followed by his wife Liuda and Daniel, a boy from the neighborhood.

They want to visit the three springs. It is said that the water of each of the springs has distinctive tastes. When they get to the place, they can see tourists’ traces: campfire ash, some pieces of paper. Tourists are not uncommon in these places. Gheorghe tells us that they come with their tents and spend a couple of days here fishing. He likes spending time with them. “All of them say that this is a nice quiet place”.

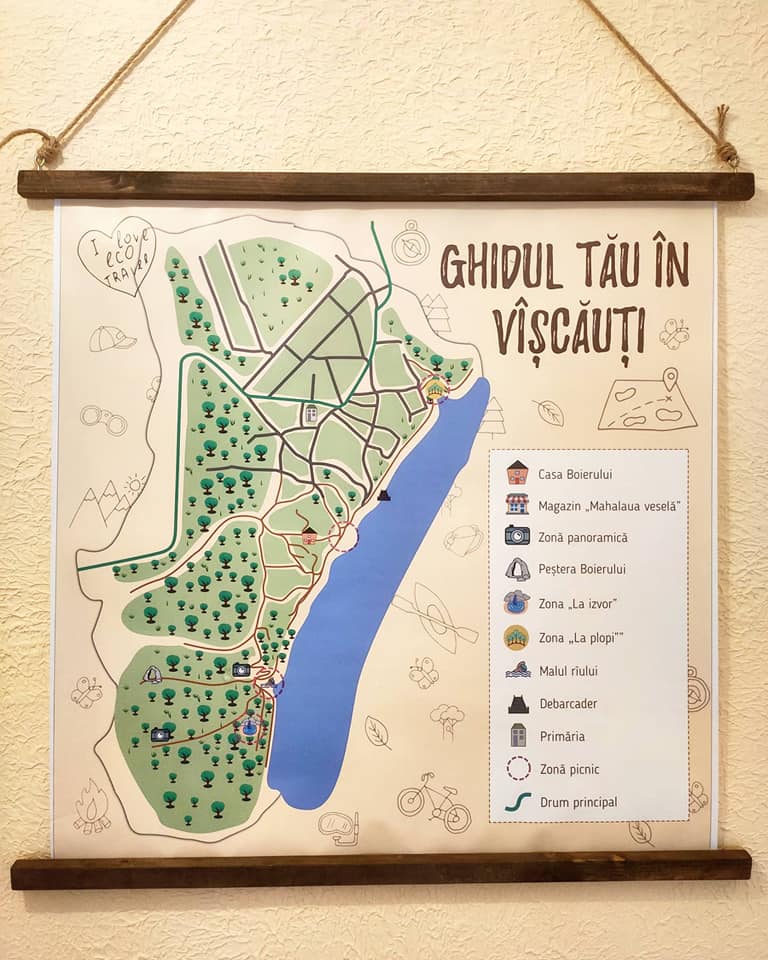

Map drawn for the tourists who visit the Boyar’s House

In Vîșcăuți you can rent a boat from the locals. You can also buy homemade bread, wine and free range chicken, fresh river fish, home grown vegetables. The village also has a beach, a picnic area, a wharf and a neighborhood called “The joyful neighborhood” due to the events organized here. From time to time, people gather here and cook fish soup or barbeque, they play some music, dance and party.

“The hill of Chirița” opens a view of Nistru river and the surrounding areas. “Now everything has dried-up… But when it’s green, the flowers there are wonderful!,” says Gheorghe.

“In Rață’s music video they showed the entire village. They filmed the forest and our meadow”, recalls Gheorghe. “There is also a song – My meadow. He sang it on TV many times,” adds Ludmila.

„Over the mountain, over the river – is my meadow,

Sometimes yearly, sometimes late – I take a walk there,

Over the mountain, over the river – flowers and roses,

Over the mountain, over the river – hidden memories.”

The lyrics to the song “My meadow”, sang by Moldovan singer Ion Rață, born in Vîșcăuți, where the music video was filmed.

Since the pandemic started, Ludmila and Gheorghe appreciate life in the village even more. “When the pandemic started, everyone was so agitated and scared. When we were in Chișinău, we would see all the ambulances and police cars throughout the entire city. But when we came here, it was like coming to heaven. When you get in the yard, you don’t need the mask any longer. We are peaceful here and we see to our chores. In Chișinău we didn’t have anything to do, except sitting on the benches outside. But here we exercise, we grow vegetables, fruits, we make canned food for winter,” Ludmila explains. She appreciates the tourists visiting the village, because the people have the opportunity to sell something to them. “They really don’t have a way to sell something in the village, no means to make a living.”

The luck and the happiness to be born at the river

Because the village is located on the banks of Nistru, the river is the one dictating the life in the region: it gives people water, it gives them food, but also leisure areas. Gheorghe remembers that especially during the soviet period he would visit his relatives on the other side of the river, in the village of Harmațca. They would barbeque under the willows near the river and then cross Nistru and continue their party under the willows of Vîșcăuți.

At the guest house, while stirring the pot roast, Lucia is humming a sad song. She is absorbed by the process and lets herself caught up in the moment:

Nistru, don’t drown me,

Nistru, don’t drown me,

Shai-rai-rai-ra, Shai-rai-rai-ra.

You don’t have the money to burry me,

You don’t have the money to burry me,

Shai-rai-rai-ra, Shai-rai-rai-ra.

“I woke up to this song. I woke up with my grandparents, with my parents, with the entire village singing it, and we learned it.” She grinds some cheese on a plate, and on another she puts some parmesan – so it’ll be tastier with the mămăliga. She puts some clay plates on the table and invites the guests.

“I am very proud to be born near the river,” says Lucia. She has happy memories of her childhood, when the winters were colder and the ice on the river could reach even 1 meter in depth. “Cars and tractors, even trucks with gas tanks would cross Nistru, driving towards the Transnistrian region,” she explains.

1 434 |

1 210 |

People live in VîșcăuțiSources: BNS, 2014 |

People live in HarmațcaSources: dubossary.ru, 2013 |

Even today, the bond between the two river banks is not lost. Lucia has relatives living in the village across the river, in Harmațca. “We have brothers and sisters, we have cousins, we are all related to each other. Because it’s a whole.”

Produced with the financial support of the European Union within the “Support to Confidence Building Measures” project, implemented by UNDP. The opinions expressed in this material do not necessarily reflect the official position of the EU or UNDP.

Economy

Romania and Moldova signed a partnership memorandum pledging to cooperate in promoting their wines

Reading Time: 2 minutesThe Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Romania (CCIR) and the National Office for Vine and Wine (NOVW) of the Republic of Moldova signed, last week, a memorandum of cooperation on organizing joint promotional activities in the markets of common interest, as the CCIR announced.

China, Japan or the USA are just some of the markets targeted by the Romanian and Moldovan institutions. The memorandum also involves advertising activities for wines from common indigenous varieties, promoting the oeno-tourist region, developing a tourist route in the two states, exchange of experience, study visits, and mutual support in identifying new export opportunities. “We are very confident that this collaboration between our organizations will lead to sustainable economic growth and a higher degree of well-being among Moldovans and Romanians,” claimed Deputy Secretary-General of CCIR, Bogdan Visan.

On the other hand, Director of the NOVW, Cristina Frolov, declared that no open competition with Romania is aimed at the governmental level of the Republic of Moldova. “This request for collaboration is a consequence of the partnership principle. Romania imports 10-12% of the wine it consumes, and we want to take more from this import quota. Every year, the Romanian market grows by approximately 2.8%, as it happened in 2020, and we are interested in taking a maximum share of this percentage of imported wines without entering into direct competition with the Romanian producer,” the Moldovan official said. She also mentioned that Moldova aims at increasing the market share of wine production by at least 50% compared to 2020, and the number of producers present on the Romanian market – by at least 40%.

Source: ccir.ro

**

According to the data of the Romanian National Trade Register Office, the total value of Romania-Moldova trade was 1.7 billion euros at the end of last year and over 805 million euros at the end of May 2021. In July 2021, there were 6 522 companies from the Republic of Moldova in Romania, with a total capital value of 45.9 million euros.

The data of Moldova’s National Office of Vine and Wine showed that, in the first 7 months of 2021, the total quantity of bottled wine was about 27 million litres (registering an increase of 10% as compared to the same period last year), with a value of more than one billion lei, which is 32% more than the same period last year. Moldovan wines were awarded 956 medals at 32 international competitions in 2020.

Photo: ccir.ro